Once upon a time, there was a world without the internet.

Can you even imagine it? No Google, Facebook, YouTube, Twitter.

In fact, 100 years ago, there was no television. No radio, either, except among a few hobbyists.

It would be 1920 before the first crackling news broadcast aired on Detroit’s radio station 8MK (which still exists as station WWJ).

But newspapers, well, they’d been around in daily format for 200 years. And it was by poring over those printed ink pages, dear reader, that people found out about what was going on in their neighbourhood, their country and the world.

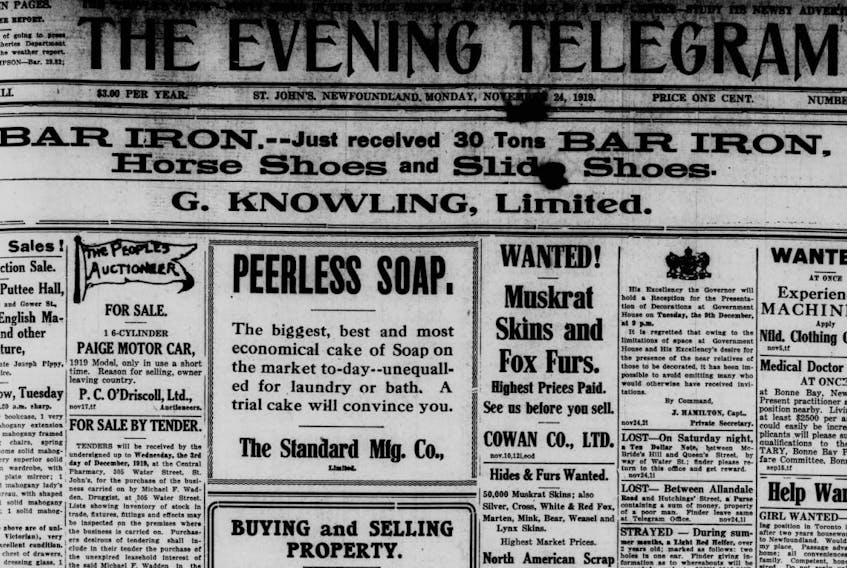

Reading an old newspaper is like time travel, with the advertisements providing as much anthropological information as the news itself.

In downtown St. John’s a century ago, businesses were trumpeting their merchandise in the 14-page Evening Telegram, with special foodstuffs brought in from America and the continent just in time for the holidays.

You can almost picture the clerks and shopkeepers bustling about, unpacking wooden crates and creating artful displays of wares.

There were new perfumes suggesting “the balmy odors of springtime,” Conchas cigars and rust-proof corsets. Moir’s cakes and chocolates, tins of Norwegian brislings and “Jack tar” pilchards from England, greengage plums and cranberries, “Xmas confectionary & biscuits,” kegs of the choicest sausages, fresh oysters, rabbits, turkeys, ducks and chickens, and “something nice for tea”: ham and tongue, veal loaf, ox tongue, finnan haddie and smoked kippers — all washed down with “Ross’s Dry Ginger Ale (the nearest thing to champagne)” or an assortment of other Aerated Drinks.

Jewellers T.J. Duley and Co. advertised a new shipment of purses. “We have just opened the latest New York creations in Hand Bags — Velvets and Silks. Beauty has been combined with usefulness to make a most suitable article.”

You can almost picture the clerks and shopkeepers bustling about, unpacking wooden crates and creating artful displays of wares.

Ladies lured by those bags might also have been tempted by the “very newest and smartest American styles” of coats at Henry Blair’s, where mink marmot furs could be had for the “bargain prices” of $130 and $170.

Ladies who could afford such fashions were likely among those advertising for household help.

Mrs. P.C. O’Driscoll on Queen’s Road used the front-page classifieds to find a “good, general girl with references,” while on Rennie’s Mill Road, Mrs. Eric Bowring was in desperate need of “A Cook, at once.” The Crosbie Hotel was looking for housemaids and waitresses, while the Cochrane Hotel was hiring dining room girls.

It’s interesting to note that in those post-war days, there was plenty of work for girls — some of it menial. Yet married women were rendered virtually anonymous for posterity’s sake because they were known by their husbands’ names.

Boys were valued for their strength and speed and were taken on as shop boys and messengers.

Sharp-dressed men flocked to Bishop, Sons & Co. Ltd., where there was a waiting list for Kuppenheimer Clothes from an American fashion house. “Ninety-five men in town are now waiting for Kupperheimer overcoats,” the advertisement boasted. “About as many are waiting for Kuppenheimer suits. And they’re all glad to wait a little while rather than to risk their money elsewhere on clothes of doubtful value.”

The news of the day was consumed with the final signatures on peace treaties that had been made at the end of the First World War. Germany was dragging its heels on surrendering 140,000 “milch” cows, as it had promised to do.

The editorial of Monday, Nov. 24, 1919 was a sharp-tongued rebuke: “With the German spirit of duplicity so cunningly developed, the babies are made the pretext for the retention of one hundred and forty thousand head of milch cows, which the wily Germans do not want to restore…”

Closer to home, “the last bucket of cement was put on the walls of the new building at Mt. Cashel at 3:45 p.m. Saturday. Bro. Ennis is to be congratulated on the excellent work done by himself and his boys.”

At Saturday mass in the Roman Catholic cathedral, an announcement had been made that at Sunday services the following week, the annual collection for Christian Brothers would be taken.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Pam Frampton is The Telegram’s managing editor. Email [email protected]. Twitter: pam_frampton

MORE FROM PAM FRAMPTON