As we have just seen, crazy things can happen in the waning days of an American presidency. As evidence, if any is really needed, I offer that strange finale of James Garfield's term as the 20th U.S. president.

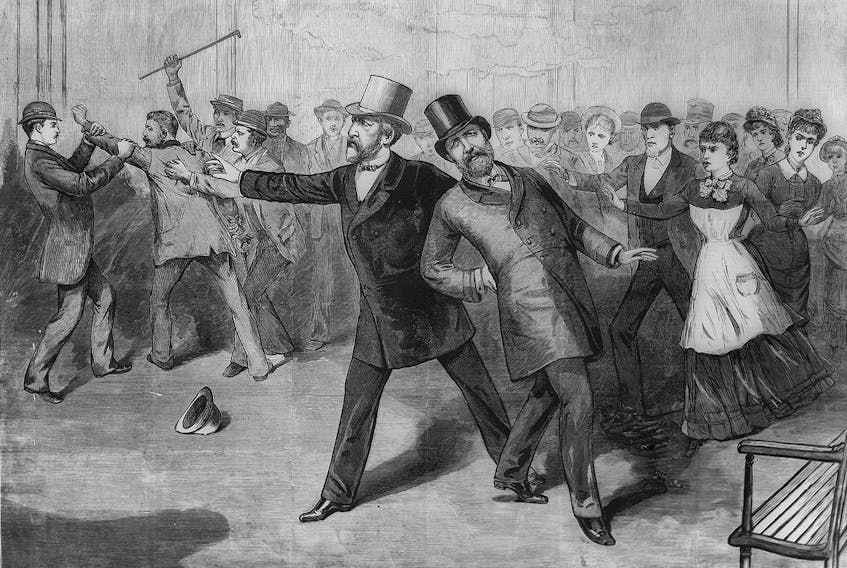

If his name means something to you, it will not be due to the monumental achievements of his presidency. It will probably be because four months after his swearing in, a deranged political failure named Charles J. Guiteau approached Garfield at a Washington train station and shot him twice, the second bullet lodging in his abdomen

It is believed that Garfield would have survived his wounds today with the kind of antibiotics and surgical techniques now available. This, however, was 1881.

According to an online piece written for PBS News Hour by medical historian Howard Markel, the doctors who attended Garfield stuck their unwashed fingers in the wound and probed around in search of the bullet, a common medical practice for treating gunshot wounds in the late 19th century.

Back in the White House, the president's medical treatment became truly barbaric.

“As the summer waned, Garfield was suffering from a scorching fever, relentless chills, and increasing confusion,” wrote Merkel. “The doctors tortured the president with more digital probing and many surgical attempts to widen the three-inch deep wound into a 20-inch-long incision, beginning at his ribs and extending to his groin.”

The wound became, in Merkel's words, “a super-infected, pus-ridden, gash of human flesh.” Yet, for a time, Garfield's condition was up and down.

Aug. 10, 1881, 29 days after the shooting, was one of the president's best days, Jared Cohen wrote in his 2019 book Accidental Presidents: Eight Men Who Changed America.

Which is why Garfield's doctor felt it OK that day to ask him to sign an extradition warrant, Garfield's only official act during the 80-day period between being shot and dying.

Now, at last, we get to the point of why I am telling us all this stuff about long-ago events in another country.

Because the warrant, which had been prepared by the state department, concerned a “minor extradition matter” over a Missouri fugitive name Gaiten Denohan.

We must depend on Cohen for the smidgens of biographical information that exist about Denohan: that he was a “notorious swindler and bogus priest with a score of aliases” who had been caught and imprisoned for forgery a year earlier.

Most importantly, that after escaping from Missouri State Penitentiary in the winter of 1881, Denohan somehow “sought refuge in Halifax Canada.”

Cohen writes that Missouri's prison warden dispatched his own son here to bring the notorious grifter back. However, according to the papers at the time, “the (Halifax) authorities refused to give him up, on the ground that forgery, the crime of which he was convicted, is not an offence for which a prisoner is subject to extradition.”

So, just to recap: an American president's dying wish was that an escaped prisoner be returned to jail in the state of Missouri; the government of tiny little Halifax, at that point likely led by mayor George Fraser, responds not a chance, thereby leaving a master of disguise and forgery, and an escape artist to wander our rain-slicked streets.

How long Denohan stayed here, what he did — even what name he went under — is anyone's guess.

Wednesday, when I asked Dean Jobb, the dean of Nova Scotia true crime writers, if he had heard of Denohan he replied, “I'm drawing a blank.”

When I typed in his name in the Nova Scotia Archives' search engine it came back with zero hits.

A quick scan of Thomas Raddall's authoritative Halifax, Warden of the North, the best history ever written about this city, found not a single mention of Denohan, or any other forger for that matter.

All of which leaves me to wonder if maybe one day Denohan just opened up a paper like this one, glimpsed a Christian name on one page and a surname on another, and created a new identity for himself.

Then, maybe he donned one of those disguises for which he was known, another bogus priest perhaps, and set out on horseback to bring fire and brimstone to the Godless folk in the backwoods of this province.

Maybe he jumped on a ship, bound for somewhere far away to resume the con man's life.

Maybe, on the other hand, he stayed right here in Halifax, where his descendants now walk among us as respectable men and women unaware of their link to another tumultuous American presidency.