October is Mi’kmaq History Month, and the Mi’kmaq people of Prince Edward Island are proud of their culture, traditions and history. However, sadly, there is a very dark piece of that history that is shared with Aboriginal people across Canada. It is not just a dark period in the history of Canada’s indigenous population; it is a dark period in Canadian history. It is the Indian Residential Schools.

The first schools opened in the 1870s and the last one was not closed until 1996 – less than 20 years ago. The schools were opened with a policy to remove Aboriginal children from the influence of their families and cultures and to assimilate them into the dominant Canadian culture. The goal was to “de-Indianize” them.

In the words of Supreme Court of Canada Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin, Canada attempted ‘cultural genocide.” One hundred and fifty thousand First Nation children passed through the residential school system, many of them forcibly removed from their homes and families, and at least 4,000 of them died while attending the schools.

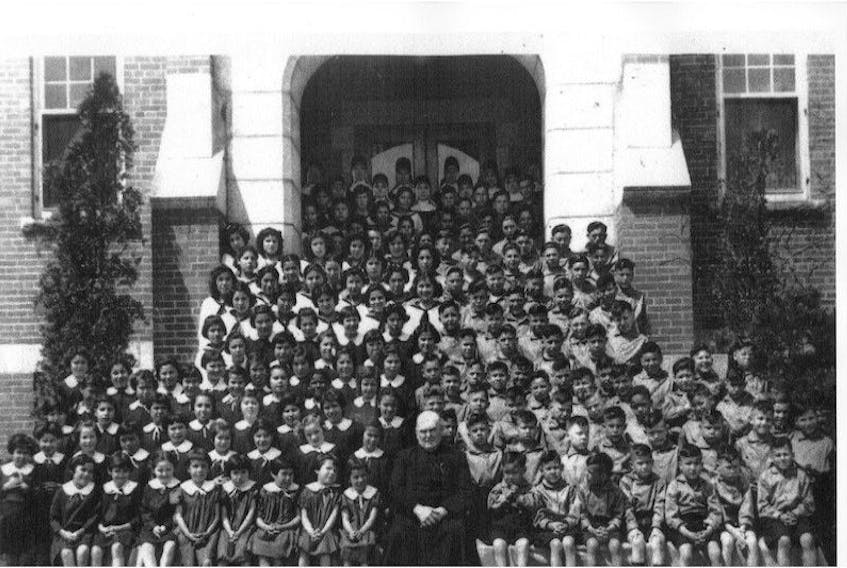

Mi’kmaq children from P.E.I. were taken to the residential school in Shubenacadie, N.S. The Shubenacadie School was underfunded, the facility was cold and leaked; hunger and malnutrition were prevalent. In addition to stripping children of their culture, identity and family heritage, they were subjected to extreme violence. Physical, psychological and sexual abuse at the hands of the school staff was all too common. There are accounts of young children being severely beaten for nothing more than speaking in their native language.

The children who attended the residential schools bear the scars from the abuse and mistreatment, but those scars were, and are, felt by the generations that followed. In 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered a public apology for the residential schools on behalf of the Canadian Government.

That same year, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established to uncover the full truth about the schools. The TRC released its report in 2015, and set out 94 “calls to action” to redress the shameful legacy of the residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation.

One of the goals was to guide and inspire Aboriginal peoples and Canadians in a process of reconciliation and renewed relationships that are based on mutual understanding and respect. The Mi’kmaq leaders on P.E.I., Chief Brian Francis of the Abegweit First Nation and Chief Matilda Ramjattan of the Lennox Island First Nation, will work tirelessly with the federal and provincial governments to ensure that the calls to action are implemented.

But the residential schools were not just a government failing, they were a societal failing. In a country that prides itself on being a world leader in human rights, it is incomprehensible that such atrocities were permitted to occur. Governments, educational institutions and professional bodies all have a role to play in achieving reconciliation.

But in order for the process to be truly successful, it requires an acknowledgment by the public at large of the history of the schools and the tragic legacy they created. It is not about blame or shame; it is about an understanding of the role of the schools in the current plight of the Aboriginal population, it is about renewed relationships, it is about education and tolerance, and it is about a unanimous commitment that such a reprehensible piece of our history must never again be permitted.

By Donald K. MacKenzie (guest opinion)

Donald K.MacKenzie is executive director of the Mi’kmaq Confederacy of P.E.I.

October is Mi’kmaq History Month, and the Mi’kmaq people of Prince Edward Island are proud of their culture, traditions and history. However, sadly, there is a very dark piece of that history that is shared with Aboriginal people across Canada. It is not just a dark period in the history of Canada’s indigenous population; it is a dark period in Canadian history. It is the Indian Residential Schools.

The first schools opened in the 1870s and the last one was not closed until 1996 – less than 20 years ago. The schools were opened with a policy to remove Aboriginal children from the influence of their families and cultures and to assimilate them into the dominant Canadian culture. The goal was to “de-Indianize” them.

In the words of Supreme Court of Canada Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin, Canada attempted ‘cultural genocide.” One hundred and fifty thousand First Nation children passed through the residential school system, many of them forcibly removed from their homes and families, and at least 4,000 of them died while attending the schools.

Mi’kmaq children from P.E.I. were taken to the residential school in Shubenacadie, N.S. The Shubenacadie School was underfunded, the facility was cold and leaked; hunger and malnutrition were prevalent. In addition to stripping children of their culture, identity and family heritage, they were subjected to extreme violence. Physical, psychological and sexual abuse at the hands of the school staff was all too common. There are accounts of young children being severely beaten for nothing more than speaking in their native language.

The children who attended the residential schools bear the scars from the abuse and mistreatment, but those scars were, and are, felt by the generations that followed. In 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered a public apology for the residential schools on behalf of the Canadian Government.

That same year, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established to uncover the full truth about the schools. The TRC released its report in 2015, and set out 94 “calls to action” to redress the shameful legacy of the residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation.

One of the goals was to guide and inspire Aboriginal peoples and Canadians in a process of reconciliation and renewed relationships that are based on mutual understanding and respect. The Mi’kmaq leaders on P.E.I., Chief Brian Francis of the Abegweit First Nation and Chief Matilda Ramjattan of the Lennox Island First Nation, will work tirelessly with the federal and provincial governments to ensure that the calls to action are implemented.

But the residential schools were not just a government failing, they were a societal failing. In a country that prides itself on being a world leader in human rights, it is incomprehensible that such atrocities were permitted to occur. Governments, educational institutions and professional bodies all have a role to play in achieving reconciliation.

But in order for the process to be truly successful, it requires an acknowledgment by the public at large of the history of the schools and the tragic legacy they created. It is not about blame or shame; it is about an understanding of the role of the schools in the current plight of the Aboriginal population, it is about renewed relationships, it is about education and tolerance, and it is about a unanimous commitment that such a reprehensible piece of our history must never again be permitted.

By Donald K. MacKenzie (guest opinion)

Donald K.MacKenzie is executive director of the Mi’kmaq Confederacy of P.E.I.