BY PETER MCKENNA: Recently, the Trudeau government announced that it would be providing up to 600 Canadian soldiers and 150 police officers to participate in United Nations (UN)-supported operations in Africa. There is something like 12 ongoing UN missions today and Ottawa is looking seriously at the Congo, Mali and the Central African Republic.

Not surprisingly, there has been plenty of chatter about Canada’s return to its traditional vocation of keeping the peace internationally. For many of us, the concept of peacekeeping and Canada has become a central part of Canadian mythmaking and middlepowerism - and a key source of national pride.

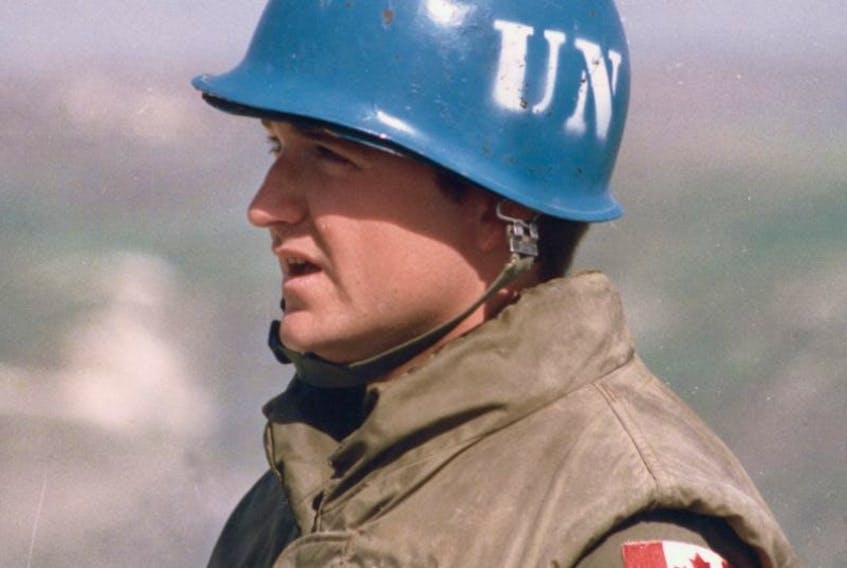

But wherever Canadian troops are deployed - and the announcement is likely to be made at the September 8th UN Peacekeeping Defence Ministerial meeting in London - this will not be your father’s peacekeeping mission. The days of classical or first-generation peacekeeping, with lightly armed soldiers implementing a ceasefire between two warring countries or parties, are long gone.

Call it what you want today: peacemaking, peace-building or peace enforcement - it is far from pedestrian. The common term, and the one most often used by the Canadian military, is more along the lines of “peace support operations.” The key point here to understand is the clear danger involved in these types of vicious, often ethnically polarized, internal conflicts.

It is worth noting that members of the Canadian armed forces have never really liked participating in old-style peacekeeping operations. They frequently detested the monotonous pace and boredom, the traffic-cop mentality, or the lack of live-fire action and training. As one grizzled army veteran once told me: “As a professional soldier, and in comparison to the medical profession, I want to be performing delicate and dangerous surgeries and not treating the common cold.”

Perhaps that view will change now that peacekeeping has morphed into peacemaking and peace enforcement. And one should not forget that hundreds of UN soldiers have been killed in Africa (especially in Mali) in the last five years.

Whether or not you agree with Canada’s return to the peace support business - and many rightly have grave concerns about potential Canadian casualties, the length and terms of its mandate, and its impact on actually resolving the internal conflicts - there are valid foreign policy reasons underscoring it.

Recall Canadian foreign minister Louis St. Laurent saying in a memorable 1947 speech: “Our geography, our climate, our natural resources, have so conditioned our economy that the continued prosperity and well-being of our own people can best be served by the prosperity and well-being of the whole world. We have thus a useful part to play in world affairs, useful to ourselves through being useful to others.”

There is no disputing that vital Canadian interests - whether in the political, economic, security or diplomatic domains - are clearly advanced by a stable world order. Even today, Canada still benefits from making itself useful to others by engaging internationally in mediation, conflict resolution and peace support activities.

Accordingly, the Liberal government is back in the multilateralism game because the former Conservative government severely damaged Canada’s credibility and respectability in international fora. And make no mistake about it; Canadian national interests are intimately connected to our active participation in international organizations like the UN.

Indeed, Canada possesses influence on the world stage by working co-operatively and collaboratively with other like-minded countries. And we can’t get other countries to do things for us if we don’t pull our weight in the world.

There is the added motivation that Canada is angling for a 2020 seat on the UN Security Council, which the Stephen Harper government embarrassingly lost in our 2010 bid. So the price to pay, in some regards, is re-engaging with the world and the member states of the UN to repair our global image and reputation.

It also doesn’t hurt that the United States is urging Canada to take on these types of military operations. Of course, we shouldn’t do it just because it would make Washington happy. But earning diplomatic credit in the bank with our most important ally and customer is never a bad idea.

In short, Canada does need to badly get back in the game internationally. Now, I’m not totally convinced that this is the proper way to do it. And, quite frankly, I’m not sure that Canadians are ready to accept the cost in inevitable blood and treasure.

But at least there is a foreign policy rationale for doing so - unlike the previous government’s all-to-frequent electoral calculations driving the conduct of Canada’s international policy.

- Peter McKenna is professor and chair of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.

BY PETER MCKENNA: Recently, the Trudeau government announced that it would be providing up to 600 Canadian soldiers and 150 police officers to participate in United Nations (UN)-supported operations in Africa. There is something like 12 ongoing UN missions today and Ottawa is looking seriously at the Congo, Mali and the Central African Republic.

Not surprisingly, there has been plenty of chatter about Canada’s return to its traditional vocation of keeping the peace internationally. For many of us, the concept of peacekeeping and Canada has become a central part of Canadian mythmaking and middlepowerism - and a key source of national pride.

But wherever Canadian troops are deployed - and the announcement is likely to be made at the September 8th UN Peacekeeping Defence Ministerial meeting in London - this will not be your father’s peacekeeping mission. The days of classical or first-generation peacekeeping, with lightly armed soldiers implementing a ceasefire between two warring countries or parties, are long gone.

Call it what you want today: peacemaking, peace-building or peace enforcement - it is far from pedestrian. The common term, and the one most often used by the Canadian military, is more along the lines of “peace support operations.” The key point here to understand is the clear danger involved in these types of vicious, often ethnically polarized, internal conflicts.

It is worth noting that members of the Canadian armed forces have never really liked participating in old-style peacekeeping operations. They frequently detested the monotonous pace and boredom, the traffic-cop mentality, or the lack of live-fire action and training. As one grizzled army veteran once told me: “As a professional soldier, and in comparison to the medical profession, I want to be performing delicate and dangerous surgeries and not treating the common cold.”

Perhaps that view will change now that peacekeeping has morphed into peacemaking and peace enforcement. And one should not forget that hundreds of UN soldiers have been killed in Africa (especially in Mali) in the last five years.

Whether or not you agree with Canada’s return to the peace support business - and many rightly have grave concerns about potential Canadian casualties, the length and terms of its mandate, and its impact on actually resolving the internal conflicts - there are valid foreign policy reasons underscoring it.

Recall Canadian foreign minister Louis St. Laurent saying in a memorable 1947 speech: “Our geography, our climate, our natural resources, have so conditioned our economy that the continued prosperity and well-being of our own people can best be served by the prosperity and well-being of the whole world. We have thus a useful part to play in world affairs, useful to ourselves through being useful to others.”

There is no disputing that vital Canadian interests - whether in the political, economic, security or diplomatic domains - are clearly advanced by a stable world order. Even today, Canada still benefits from making itself useful to others by engaging internationally in mediation, conflict resolution and peace support activities.

Accordingly, the Liberal government is back in the multilateralism game because the former Conservative government severely damaged Canada’s credibility and respectability in international fora. And make no mistake about it; Canadian national interests are intimately connected to our active participation in international organizations like the UN.

Indeed, Canada possesses influence on the world stage by working co-operatively and collaboratively with other like-minded countries. And we can’t get other countries to do things for us if we don’t pull our weight in the world.

There is the added motivation that Canada is angling for a 2020 seat on the UN Security Council, which the Stephen Harper government embarrassingly lost in our 2010 bid. So the price to pay, in some regards, is re-engaging with the world and the member states of the UN to repair our global image and reputation.

It also doesn’t hurt that the United States is urging Canada to take on these types of military operations. Of course, we shouldn’t do it just because it would make Washington happy. But earning diplomatic credit in the bank with our most important ally and customer is never a bad idea.

In short, Canada does need to badly get back in the game internationally. Now, I’m not totally convinced that this is the proper way to do it. And, quite frankly, I’m not sure that Canadians are ready to accept the cost in inevitable blood and treasure.

But at least there is a foreign policy rationale for doing so - unlike the previous government’s all-to-frequent electoral calculations driving the conduct of Canada’s international policy.

- Peter McKenna is professor and chair of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.