An insatiable sense of curiosity and strong opinions have always been character traits of Prince Edward Islanders, and no doubt are two of the reasons Charlottetown residents have always been loyal newspaper readers.

When it comes to Islanders and their opinions, perhaps city poet Milton Acorn summed it up best when he said, “The Island’s small ... every opinion counts.” The Island’s first newspaper was the Royal American Gazette and Weekly Intelligencer of the Island of Saint John, which was published in Charlottetown in September of 1787. It lasted less than a year but was quickly followed by many more, such as the Royal Gazette and Miscellany of the Island of Saint John, the Prince Edward Island Gazette and the Weekly Recorder of Prince Edward Island.

“For many homes, outside of the Bible, they might not have had much else to read but the paper,” says Island historian Ed MacDonald, referring to the Charlottetown of the 1800s.

Today’s media world is complex, filled with every imaginable technological option, from print and radio to TV and the blossoming Internet world.

But in Charlottetown’s early years, newspapers were the only game in town. If someone had a message to deliver, their options were limited. They could climb onto a soapbox and shout at passersby. Or, they could rent a hall and put their oral powers on display. But if they had the where with all to do it, the most effective option was to launch a newspaper.

“If you wanted to put your voice out there, if you wanted to be read, there was no radio, no TV, there was no medium of advertising that was going to put your views in every hall and school in the province,” said MacDonald. “The newspaper was your voice. And a lot of people were there to listen.”

The UPEI professor and author of If You’re Stronghearted, published in 2000, says although the early newspapers were gobbled up by the readers, they needed sponsors to survive.

“They were the organ of a particular kind of viewpoint,” MacDonald said, explaining that the newspapers of the day were affiliated with a religious or political point of view, or some other cause.

This was a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the movement’s followers provided a predictable and loyal audience.

However, those not party to the newspaper’s philosophy were unlikely to support it.

The Guardian was a bit of a late starter in Charlottetown’s newspaper industry and through the years faced stiff competition from such papers as the Patriot, the Examiner and the Herald.

But it has outlived them all and today is the city’s only daily.

The paper’s roots go back to the 1870s and Rev. Stephen G. Lawson, a Presbyterian minister. For some years he published a paper called The Presbyterian.

That name was later changed to The Protestant Union, but the name change didn’t help the paper’s finances.

Lawson surrendered it to Rev. William R. Frame, who changed the paper’s name to The Guardian around 1887. Frame avoided the extremes in politics of his predecessor and strengthened the paper's hold upon the public.

At his death, on June 30, 1888, John L. McKinnon, an experienced journalist, took charge of The Guardian as general manager and editor. In June of 1889 he handed the reins over to Benjamin D. Higgs. The paper flourished under Higgs' management and was changed from a weekly to a daily on Jan. 27, 1891.

In February of 1896, J.E.B. McCready, formerly of Saint John, N.B., who had been an outstanding member of the Press Gallery at Ottawa, took editorial charge. Following Higgs’ death, J.P. Hood acquired a controlling interest in The Guardian Company and continued it for some years.

In 1912, the Island’s Conservative party bought The Guardian plant and and engaged James Robertson Burnett as editor and manager. Trained as a journalist in Scotland and British Guiana, Burnett brought improved business methods to The Guardian and greatly increased its circulation.

He was one of the pioneers in the establishment of The Canadian Press.

With him as associate editors were McCready and D.K. Currie and, later, Frank Walker. Walker was referred to as “Mr. Hansard” because of the accuracy and objectivity on his reports from the P.E.I. legislature.

By this time, the paper was owned largely by one leading Conservative, Sir Charles Dalton, founder of the silver fox industry and later lieutenant governor of the province.

About 1921 the Dalton interests were sold to W. Chester S. McLure (then a Conservative MLA and later MP for Queens) and Lt.-Col. D.A. MacKinnon, D.S.O. The only other stockholder was Burnett. McLure became president of The Guardian Publishing Company and MacKinnon the secretary.

On April 28, 1923, a fire destroyed The Guardian plant and building, then on the corner of Kent and Great George. For some time the paper was issued from Burnett's residence on Kent Street and printed on The Patriot press.

The Temperance Hall, a stately century-old building on the corner of Prince and Grafton streets, was acquired and the paper continued to be published there until 1956, when it moved into its present location on Prince Street.

Around 1948, McLure and Col. MacKinnon sold out to Burnett and his sons, Ian, Bill, Lyn and George, who were associated with him in the business. Burnett died on June 12, 1952.

The Burnetts relinquished their financial interests to Thomson Newspapers Limited in December 1953, and The Guardian became the first member of the Thomson newspaper group in the Atlantic provinces. It was joined later by The Patriot and both papers were published out of the Prince Street location until the mid-1990s when The Patriot closed on June 9, 1995. The Patriot had begun publishing on July 1, 1864, and had a reporter at that year’s famous Charlottetown Conference.

Since being bought by Thomson in the 1950s, The Guardian has had many off-Island corporate owners. In October of 1996, it was purchased by Southam Inc. A short time later, the paper came under the ownership of Hollinger, which was controlled by Conrad Black.

The corporate shuffle continued late in 2000 when CanWest Global Communications of Winnipeg purchased the newspaper. In August of 2002, the newspaper was purchased by Transcontinental Media of Montreal.

The present owner, SaltWire Network, purchased the newspaper in April 2017.

Today’s Guardian, like the ones of old, still carries plenty of news about politics but coverage is non-partisan, unlike the old days. From 1912 into the 1950s it was unabashedly Conservative in its political leaning, as opposed to its rival the Patriot, which was the Liberal paper of record.

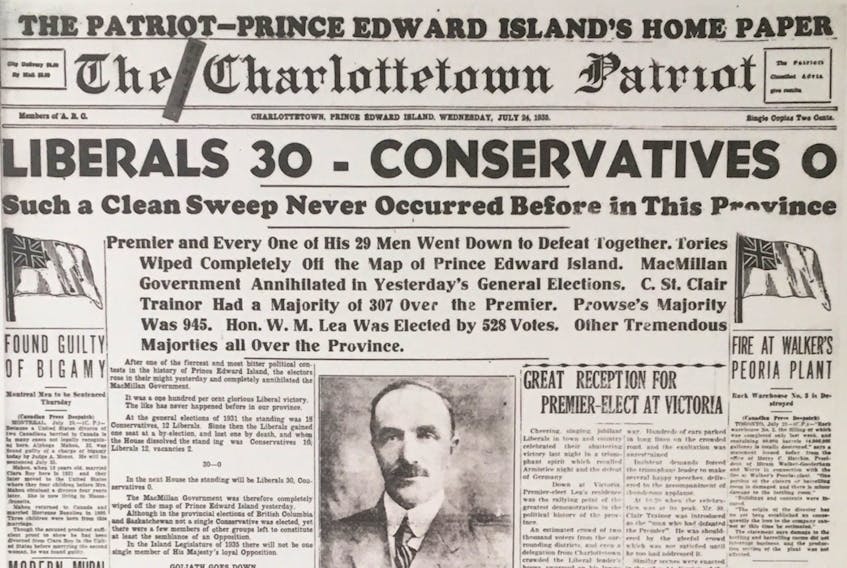

The two opposing points of view must have made for some interesting reading. The reporting on the July 1935 election is a classic example of how the two papers’ editors were often seeing two different worlds. The election was a rout for the Liberals. In black, bold letters, the Patriot proclaimed: “Liberals 30 - Conservatives 0.”

A smaller, but no less exuberant heading, said: “Tories wiped completely off the map of Prince Edward Island. MacMillan government annihilated in yesterday’s general elections.”

That day’s Guardian was much less enthusiastic about the outcome.

“Island votes for Liberal dictatorship,” the headline read. A smaller heading said, “Exploiting depression and unemployment grievances, Liberals yesterday achieved clean sweep in every constituency. Conservative electors deprived of any voice in legislative assembly.”

Most newspapers do a much better job of recording the daily history that is happening all around them then recording their own. The Guardian is no exception in this regard.

Because the newspaper does not document its past as much as it should, unfortunately it would be possible to stand in the newsroom — or any other part of the building — today and shout out important names from earlier years like Frank Walker, Vere Beck, Pius Callaghan, Bill Hancox , Bill Burnett, Ralph Cameron, Neil Matheson, Walter MacIntyre and Lorne Yeo and in many cases be met with blank stares.

And although few details are written down about the antics that have occurred in newsrooms through the years, some unwritten anecdotes refuse to die.

There’s the one about a reporter, whose nickname had something to do with the fact he was missing a finger or two, who was assigned to cover a legion convention and didn’t come back for three or four days.

The newsroom has also had its share of curious visitors, both two-legged and four-legged ones, such as a billy goat wearing a straw hat, several bags worth of dormant bats and a cheetah.

Stories about flying typewriters also refuse to die. One story has it that an upset journalist tossed a typewriter through the second floor newsroom window one night. Another story involved a typewriter being thrown down the stairwell in anger.

Bad temper? Far from it.

They’re just examples of the passion that has filled the hearts of men and women in the newspaper industry through the years who have put the news out on the street six days a week for all to read.

-Written by Gary MacDougall, a former managing editor at The Guardian.