With the cessation of hostilities on Nov. 11, 1918, the question of when “the boys” might come home became the chief preoccupation in many Island households, as it was, of course, among the soldiers themselves. The Guardian counselled patience in a Christmas Eve editorial, predicting — accurately, as it would turn out — that: “it will require nearly a year, perhaps all of it, to bring them all home”.

Some Islanders, however, had already been blessed with a much shorter wait. As The Guardian delightedly reported on its Dec. 17 front page, the previous evening had seen the arrival of more than 50 Island soldiers returning from overseas at the Charlottetown train station: the premier and the mayor of Charlottetown joined a military band and a cheering crowd in welcoming the soldiers, and a volunteer convoy of automobiles and carriages transported them to a reception organized by the Great War Veterans Association. Similar scenes were reported a few days later, when the arrival of another sizeable group of returnees.

Amidst the jubilant reunions — or eager anticipation of same — and the pain of those whose loved ones were dead or irreparably broken, some early efforts were being made to reckon the cost of it all. The Guardian’s assessment of the economic toll was surprisingly insouciant — “largely a matter of book-keeping,” in the words of a Dec. 2 editorial — but there was no disputing the broader conclusion: “Canada’s real loss, her irreparable loss, is that of her sons, over 50,000 of whom have laid down their lives …”.

Carrying on from this point, The Guardian, to its lasting credit, was the first organ to attempt a comprehensive public reckoning of the Island’s war casualties. The issue of Dec. 20 carried a Roll of Honor, covering one and a half full pages, listing Islanders who had been killed in action, along with those who had died of wounds or died on military service or who had been wounded, taken prisoner, reported missing or medically discharged. The total came to more than 1,600 names, including some 428 dead. Horrific as this tally was, it was almost certainly an underestimate — at least one later calculation would put the Island death toll at nearly 800 — and, indeed, an editorial note in the same issue asked readers to alert The Guardian to any omissions.

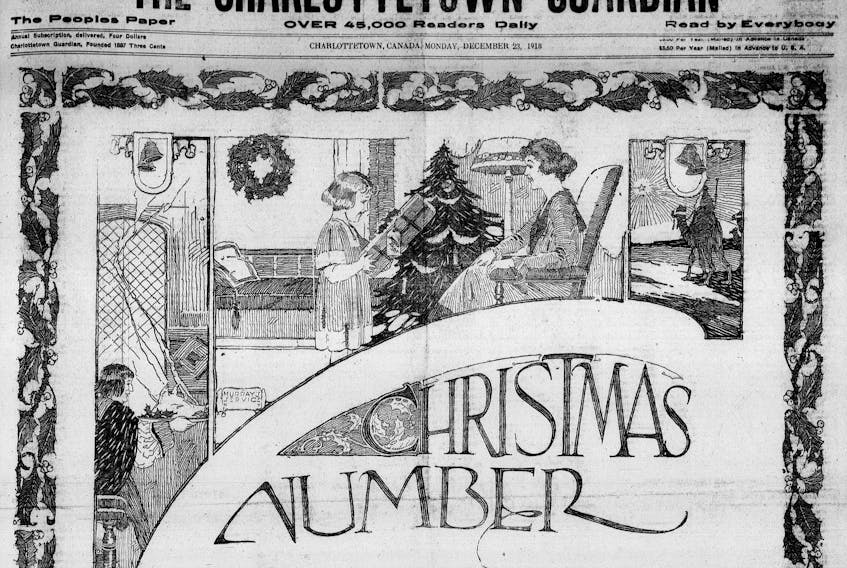

Three days later, The Guardian printed its annual “Christmas Number”: in keeping with traditional practice, the issue’s front page was wreathed with images of yuletide cheer; on pages two and three, without any word of explanation or warning, the Roll of Honor was printed again. We cannot know, a century later, whether this was a deliberate attempt to shock readers or simply an incongruous editorial decision, but we might reasonably suggest that The Guardian team was, itself, somewhat in shock, amidst an extraordinary swirl of events and emotions.

On Christmas Day, 1918, the lead editorial opened: “The events of the past four and a half years …. and the glorious halo of peace that ushers in this day are too profound, too stupendous, too full of unutterable thoughts for merriment and, for many, too full of sadness for happiness … .”

The paradox of history is that the even as the passage of time allows more opportunity for research, reflection and discussion, it also carries us inexorably further away from the events we might seek to understand. Like Scrooge, we may feel ourselves bewildered and frustrated with “shadows of the past”. The daily challenge our ancestors of a century ago have left us is to learn — in the apt words of a Guardian editorial, “Lest We Forget,” for Dec. 18, 1918 — “what we can understand of their story”. We can be profoundly grateful for the efforts of The Guardian — however imperfect and incomplete — to record part of the story and for the technology and generosity of vision that have made the newspaper’s pages from that momentous era freely available to us online.

Even if we find these digital shadows and spirits flawed or strange or mystifying, we can still appreciate that they have lessons to offer and ask ourselves how to apply these lessons when we awake each morning. One hundred years ago, Islanders — whether on the battlefield or at home — faced unprecedented events so shocking and terrifying that it would scarcely have been less traumatic if ghosts actually had visited them in the night.

How confident are we — individually or collectively — that we might do better than they when confronting an unimaginable horror?

Simon Lloyd is librarian responsible for the P.E.I. collection at the University of Prince Edward Island Robertson Library's University Archives and Special Collections. This is the last of a monthly series of lookbacks at the First World War he has provided since August 2014, drawing on the historic issues of The Guardian available online at islandnewspapers.ca. He thanks The Guardian and the Robertson Library for the opportunity to share these stories.