There are many lessons to be learned from the Second World War.

Gabrielle Cheverie is doing her bid to impart some of them.

“Part of the curriculum is Canada’s involvement in the Second World War,” Cheverie said of her Grade 8 social studies class at New Glasgow Academy.

“I always try to bring in some local stories to make it more interesting to the kids and more realistic to them. That was one of the stories that I had learned about with a good local connection, one of the stories that I like to tell.”

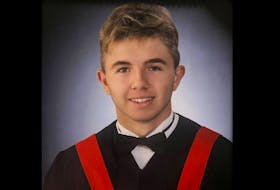

Cheverie has been teaching for nearly two decades and every year she shares the story of fellow Pictou County resident Bill Baillie, an infantryman born in Welsford who stormed onto Juno Beach in Normandy on June 6, 1944, as a sergeant major with the North Nova Scotia Highlanders.

RELATED: North Nova Scotia Highlanders at the sharp end of D-Day invasion

“The Baillies are a big family in Pictou and the students will often go home and find that they have some kind of connection to the story as well.”

The students at New Glasgow Academy feed into the North Nova Education Centre for their high school years and Cheverie says it’s no coincidence that the high school shares the name of the fabled regiment.

Cheverie had the opportunity last summer to go to the Juno Beach Centre in France as part of a teacher’s institute.

A Nova Scotia flag flies on it

“We went for just under two weeks last year, starting in Belgium and ending in Paris. We did World War I and World War II sites. I got to visit the Bill Baillie School, which was really a thrill.

“It was really special and you can really feel that strong connection that they feel with us. We kind of forget but they don’t forget because it is so much part of their culture. It says Bill Baillie School and there is a Nova Scotia flag flying on it. When we went into the school grounds, there is a little log cabin built there and it says Pictou on it. To them, it’s a very important part of their story.”

It’s also a very important part of Brian Baillie’s story.

“My father’s unit came in on Authie,” said Brian Baillie, the ninth of 11 children that his father and Scottish war bride Frances Lawrence parented in River John, Pictou County.

“They noticed that everything was going horribly wrong, the tanks were lighting up like roman candles. He happened to glance over to the left flank and he saw Nazis in camouflage trying to circle around his unit. He had a good idea of what was going on and he told his men there is only one way out. ‘We are going to crawl on our bellies from Authie all the way to Buron. That’s the only way out of here.’

"So that’s what they did. He basically saved his unit from getting encircled. The problem was that the rest of the North Novas Company C had dug in in an orchard and basically fought to the last man. Others were captured and numerous killed in the fields at Authie. Basically, it was their baptism by fire.”

Ray Coulson, curator of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders Regimental Museum, talks about Bill Baillie's legacy in the video, above.

Crawling with their rifles and 30 or 40 pounds of kit on their backs, knowing that Nazis were circling around in the grain field, Baillie led his troops almost two kilometres to Buron.

Brian Baillie, 55, said his father was 24 when he enlisted with the North Novas, having been a mine foreman in northeastern Quebec.

“He was the right age. He was old enough to look at these younger guys and make things happen. The other thing was that he was big, he was a big man. You can see pictures of him and you say he really stands out. They were going to listen. They respected him. Like my mother said, in a lot of cases, he was more like a father to these guys than a commanding officer or the guy in charge.”

Bill Baillie’s younger brother, Don, was fatally wounded on June 7 at Authie. Nearly a month later, the North Novas attacked, retook and liberated Authie. Still, a number of the North Novas felt bad that they had destroyed the school in the process. Years later, several of them got together to help rebuild the school.

Story of war and friendship lives on

In the early 1980s, Bill Baillie made the first of 10 or more trips back to the area. He met the villagers and on one of the ensuing D-Day anniversaries, the senior Baillie made a presentation of money raised by the North Novas for the school. Baillie told his former battlefield comrades that they were going to continue to contribute money to the school every year.

“The consensus in the room was that if it’s good enough for Bill Baillie, we’re doing it,” his son said. “They were that bonded to him.”

On pursuant trips, he would pop into the school and tell the students through an interpreter his story of Authie. After Baillie died in 2002, the school was named for him, École Bill Baillie.

Brian Baillie and his siblings have made several visits to the area.

“Teachers there tell the story to the students. They have the cap that he wore, the cap badge, the medals and the painting of him so they get to tell this is what actually went on here. Of course there are numerous folks around there who were children during the occupation and they also go to the school and tell them this is what happened.

“They actually teach the children the history because of course we’ve never had our country invaded or occupied. For them it was a real thing. They were occupied and they were treated horribly. For them, it’s real history. It’s tangible. Their grandparents can actually tell them. If someone was giving the Nazis a hard time in the street, they’d pick one and they’d shoot them right on the spot.”

Cheverie is trying to bring that history home.

“I do the whole story but I try to make that North Nova connection,” Cheverie said. “When I was there last summer I did some grave(stone) rubbings of some of the men from Pictou County and from town here. When I show those to the students and they see the names, they can say this man lived on Almont (Avenue) and they can say, my grandmother lives there. I live there. They can’t believe those kinds of connections.”

Cheverie has another peripheral connection to the area. James Moss, a 22-year-old Stellarton soldier, was one of the 20 captured Canadians murdered in the garden at Abbaye d’Ardenne near Caen in the immediate aftermath of the Allied invasion of Normandy. Moss was best man at the marriage of Cheverie’s grandparents, Watson and Anna MacLeod, on July 3, 1942.

Brian Baillie has been to Authie several times and says the connection of walking on the beaches and the inland battlefields where his father fought is palpable. But he said few can understand what his father and the North Novas experienced, making past D-Day anniversary celebrations and other veteran get-togethers so important.

“A lot of them were thrown back into small communities, there was nobody else there,” he said. “Nobody else gets it. The hell they went through and the big thing you’d see as soon as they saw one of the other guys was the big beaming smile. Like they all knew a secret and they weren’t telling anybody. Among themselves, they knew the other guy understood.

“Who today can say what they do can change the world? They could. They did.

“Him and all of them, I’m very proud of them.”

D-DAY AT 75: Remembering the heroes and sacrifices of Atlantic Canada:

- VIDEO: The road to D-Day

- Why a school in France is named for a Pictou soldier

- U-boat hunter Roderick Deon returns to Juno Beach for D-Day

- Sound of gunfire rang in P.E.I. soldier’s ears

- North Nova Scotia Highlanders at the sharp end of D-Day invasion

- STORY MAP: Follow the D-Day experience of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders

- 12 North Nova Scotia Highlanders murdered at Abbaye d’Ardenne

- ‘It was noisy as the devil,’ says St. John’s torpedo man

- 59th Newfoundland Heavy Regiment was eager to do its part

- A P.E.I. dispatcher’s long, uncertain journey to Normandy

- LAURENT LE PIERRÈS: D-Day invasion was best birthday present for my Dad

- ‘Sight of our boys being blown up ... wouldn’t leave my mind:’ Bedford veteran, author

- Dartmouth veteran's first combat mission was D-Day invasion

- Halifax air gunner had bird’s-eye view of D-Day

- ‘We had everything fired at us but the galley sink’: Yarmouth County veterans share war and D-Day memories

- New Waterford veteran has lived good life after surviving D-Day invasion

- JOHN DeMONT: An old film clip of D-Day shows the nature of courage

- D-Day landing map’s origins a mystery to army museum historians