Part Two of a four-day series by journalist Aaron Beswick looks at how Nova Scotia became so tied to Northern Pulp and what would happen if the pulp mill shuts down. Tomorrow: The economic threat and the strain it's put on the local community. Read Part One here.

Coming out of high school, Justin Carter wasn’t sure whether to follow his dad into the woods.

“The rhetoric I heard, even from my teachers, was that the forestry business would be dead in 10 years,” said Carter, now 28.

“That there wasn’t any future in it.”

But when Justin graduated from Amherst Regional High School, Darrin Carter had a blunt message.

“I told him, you can do whatever you want with your life except hang around the house,” recalled Darrin.

“If you graduate and don’t have anything lined up, you’re coming with me until you do.”

Mechanically inclined by nature, Justin went on the forwarder — a giant eight-wheeled machine that ambles about cut-over ground, picking up logs and sorting them in piles for the endless parade of 18-wheelers that follow Darrin Carter Logging Ltd. to the woodlots of northern Nova Scotia.

As his skills improved, Darrin moved his son to the more complex pieces of equipment, each worth over half-a-million dollars, that form the trinity of industrial forestry operations in Nova Scotian woodlots:

· The tracked feller buncher, which grabs a clump of tree in its maw, saws them off at the butt and lays them down in a tidy pile.

· And the processor, which follows closely behind to pick up each tree, limbing it and sawing off logs to length.

On each piece of gear, Justin learned to quickly assess each tree to maximize its potential for profit — softwood between four and six inches in diameter gets limbed and cut for studwood mills like Irving’s outside Truro. Larger-diameter softwood logs that are clear of rot get cut to longer lengths for other mills such as Williams Brothers in Barneys River or Elmsdale Lumber.

Top-quality hardwood heads to Groupe Savoie in Westville, while twisted or rotten hardwood often goes for firewood.

Small or misshapen spruce and fir go into the pulpwood pile.

“When I became a foreman, my job was a lot of walking around and I started to see how areas regenerate and that there is a future here,” said Justin, 28.

“I’ve cut areas that my father cut before and my grandfather (Aubrey Carter) cut before him.”

The shadow over the woods industries

But that future has a dark cloud over it.

“If Northern Pulp shuts down, we’re done the same day,” said his father.

The family’s 53-year-old patriarch, Darrin, was between the two crews run by his sons fixing machines and co-ordinating future jobs.

Although industrial forestry has many critics in this province with justifiable concerns, it is a significant part of the rural Nova Scotian economy.

One that has actually been doing fairly well over recent years.

And it is made up of people like the Carters.

“River Hebert, Oxford, Pugwash, Amherst …” Darrin lists where his 18 employees call home.

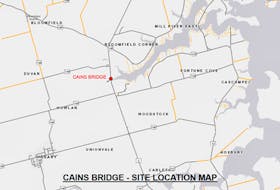

The Carter family, of East Leicester, Cumberland County, runs one of the highest-producing forestry operations in this province — spending over $2 million annually on payroll, fuel and equipment. While Justin’s crew was cutting a mixed stand of balsam fir, spruce and some short-lived hardwoods off private land in Greenfield, Colchester County, earlier this month, his brother Coady’s crew was working on Lynn Mountain, near Springhill.

“I never hung my head when anyone asked what I do,” said Darrin, who dropped out of school at 16 to start running a skidder with his father.

“I’m proud to work in the woods. Damn proud.”

They also hear about what is beginning to resemble a stalemate between Northern Pulp and those opposed to its proposed effluent pipe into the Northumberland Strait.

And they hear the debate about what might happen to Nova Scotia’s highly integrated forest industry if Northern Pulp shut down.

To many who make a living from forestry, the answer is plain.

“You would see sawmill closures and we would be among them,” said Eric Williams.

He and his siblings co-own Williams Brothers Ltd. in Barneys River, which employs 26 people in rural Pictou County.

About 150 kilometres away, Elmsdale Lumber president Robin Wilber was even more blunt.

“About 60 seconds,” he said of how long his mill, which employs 50, would survive a Northern Pulp shutdown.

The reason is the interconnectedness and tight margins of this province’s forestry industry.

All those tractor-trailers following the Carter family around head in different directions after they leave the woods. Most mixed stand woodlots have seven or eight different products destined for studwood mills, random length sawmills, pellet mills, firewood processors, hardwood chip exporters and pulp mills.

On average, 30 per cent of what the Carters cut in a year goes directly to Northern Pulp.

But a large portion of the trees sent to sawmills end up at Northern Pulp as a byproduct of lumber production.

Fates intertwined

It took three visits to Barneys River to catch Eric Williams when he was coming in the door rather than heading out.

“They don’t get what this is going to do to all of us because the general public doesn’t understand how forestry works,” said Williams, arriving back from a quick 300-kilometre trip to the Musquodoboit Valley to get a bandsaw blade sharpened.

“And none of us have time to be talking about it on the radio or on the internet.”

Williams Brothers doesn’t make the list of this province’s big four sawmills. According to the Registry of Buyers produced by the Department of Lands and Forestry, Harry Freeman and Son Ltd. in Greenfield, Queens County; J.D. Irving’s mill in Valley, Colchester County; Ledwidge Lumber Co. Ltd. in Enfield; and Scotsburn Lumber Ltd. in Pictou County each purchased over 200,000 cubic metres of wood last year to make lumber.

All those mills do business with Northern Pulp — purchasing logs from harvesting operations run by the mill and/or selling them wood chips.

So do many of the dozens of smaller mills.

Port Hawkesbury Paper runs its own logging operations and chips round wood to feed most of its softwood needs. Meanwhile 90 per cent of the million tonnes of wood purchased by Northern Pulp annually is chips, largely produced as a byproduct of making softwood lumber.

In this low profit-margin industry, everything is a product.

The large spruce logs that arrived at Williams Brothers early in December were first fed through toothed wheels that removed the bark.

That goes for hog fuel — to be burned in the boilers of pulp mills.

Next the logs went through a massive spinning blade.

The sawdust is collected and sold primarily to farmers for animal bedding.

The slabs off the sides headed through a chipper and then were blown into a separate pile outside.

Though his mill sells its chips to Port Hawkesbury Paper, Williams doesn’t think that would protect him from a drastic market contraction should Northern Pulp close.

“Everybody has a different agreement because they negotiate their chips and hog fuel with pulp prices and there may be logs as part of that,” said Williams.

“But let’s say you’re getting $60 a tonne for your chips and $16 a tonne for your hog fuel, that’s a big part of your profit margin.”

Elmsdale Lumber sends four tractor-trailer loads of chips a day to Northern Pulp.

“Now, if you take Northern Pulp out, there’s not really a market and those chips become a liability that’s piling up,” said Wilber.

“So in a month you would have 100 tractor-trailer loads stacked up. That would create another environmental issue due to leaching from that pile.”

After years of decline, the province’s sawmills have benefited from a rebound in the United States housing market that has sent the price of lumber up.

Production has increased from three-million board feet four years ago to nearly five million last year.

Meanwhile, a decrease in pulp and paper production caused by the closure of the Bowater Mersey mill near Liverpool and one of the two paper machines in Port Hawkesbury has meant the total provincial harvest has been tracking down from a high of just under seven million cubic metres in 2004 to about 3.5 million cubic metres in 2017.

“What you also have to keep in mind is that if Northern Pulp closed, you would also see an instant drop in the value of woodlots,” said Craig Tupper, forester for the Athol Forestry Cooperative.

“In rural areas woodlots often serve as people’s bank accounts, their rainy day fund or a back up for when times get hard.”

His own 80-acre woodlot is also a bank account — he’s been managing it so that when his eight-year-old is ready for college, it will be ready to be cut.

Tupper’s organization represents 250 small private-woodlot owners in Cumberland County who, combined, own 50,000 acres of land.

He develops management plans with land owners and attempts to push silviculture work that promotes the long-term development of the woodlots through thinning, selection harvests and planting. However, that work is funded through a levy placed upon each tonne of wood purchased by registered buyers.

Back in the woods, Carter isn’t sure whether he owes on three or four of his eight machines.

He learned early that debt is just a part of business.

At 18, he dove in and bought a forwarder, then five years later he borrowed $310,000 to buy a feller buncher.

“I didn’t sleep many nights,” said Carter.

“Getting some debt is the best thing there is to get you out of bed in the morning.”

He’s seen the vicious ups and downs of an industry whose production and pricing charts resemble the readings of a heart monitor.

But over nearly four decades in the woods, the current impasse with Northern Pulp is the biggest threat yet to the entire industry.

“If it was me, I would have got out years ago,” said Carter.

“But I stay in it for my sons and my employees. I don’t know what’s going to happen now.”

RELATED: