With the gear packed and the boat and truck fuelled, the Campobello Whale Rescue Team was waiting on a phone call Monday morning.

“The hurry up is done, now it’s the waiting,” said Moira Brown, research scientist attached to the team.

On Saturday afternoon, a right whale with rope wrapped around the base of its tail was spotted 64 kilometres northeast of Miscou Island by the crew of a coast guard vessel. Brown’s team was waiting for the whale, which was swimming despite the entanglement, to be spotted by one of the planes out looking for it.

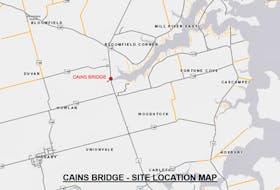

If the whale was spotted again the team planned to hit the road, driving seven-and-a-half hours to Shippegan, N.B. The attempted rescue was tentatively scheduled for Tuesday morning if the whale could be found within a reasonable distance from land and sea conditions were favourable.

As they waited, the team reviewed pictures taken from the coast guard ship of the entanglement and discussed strategy. Saving these giants is dangerous.

Veteran team member Joe Howlett was killed while freeing one of the animals in 2017 — the last bad season for the whales.

On this trip, they would have local fishermen aboard who received classroom training last winter. This would be their apprenticeship on the water as the crew from the Bay of Fundy seeks to create a new team in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Because the Gulf is where humans and right whales are once again on a collision course.

As Brown’s team was waiting to try a rescue on Monday morning, a team of veterinarians from the University of Prince Edward Island and Universite de Montreal were cutting apart a right whale on the Gaspe Peninsula that had been towed there by the CCGS Corporal Teather the day before.

As with the necropsies performed in Petite Etang (north of Cheticamp), Miscou, N.B. and Norway, P.E.I. already this season, they’ll be looking to find out why the animal died.

At least two of the six whales found dead in the Gulf this year appear to have been killed by ship strikes. That’s despite a requirement that larger vessels transiting the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence stay below 10 knots (about 18 kilometres per hour).

An area of the gulf frequented by right whales was closed to the lucrative snow crab fishery this season and last. And when regular aerial patrols spotted one of the whales anywhere in the gulf this year, the area around it was automatically closed to fishing for two weeks.

Last year the measures seemed to work, with no right whales found dead in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. But this season the bad news keeps piling on.

For Brown, who has spent a long career researching the whales and working with government and industry to protect them, hope isn’t lost. Because we’ve been through this before.

Vessel strikes and fishing gear entanglements in the Bay of Fundy saw the population of the slow moving whale drop to around 300 in the 1990s. Researchers, government and industry worked together to change how people work on the bay during the season when right whales come north to gorge themselves on tiny fatty crustaceans called copepods.

Shipping routes were moved away from prime feeding grounds near Grand Manan and other restrictions were put in place. The whale population had been rebuilding.

But then the whales stopped showing up in the Bay of Fundy during the summer months and instead heading further north to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. It appears that there are fewer copepods in the Bay of Fundy and the whales were driven farther afield to find food.

“Which is good that they were able to go find food,” said Brown.

But that also sees the whales swim through the Cabot Strait — the major transit route for all shipping that connects the Great Lakes to the wide world. There’s also an immense amount of rope and buoys attached to snow crab traps dropped toward the middle of the southern gulf, and gear for the lobster fishery all along the coasts of the five provinces that border the waterway.

So now industry, various government departments and scientists are learning again.

Ropeless fishing gear, that sees the trap release its buoy from the bottom when the fishing boat it belongs to approaches, is being tested in the Gulf. And the fines for vessels violating speed restrictions went up from 2017, when there were more than 500 violations, to its current maximum of $25,000.

“But evidently more still needs to be done,” said Brown.

She points to the fact that at least one of the whales killed by blunt force trauma symptomatic of vessel strike was spotted outside the speed restriction zone on the eastern side of the Cabot Strait separating Newfoundland and Cape Breton.

“A good step would be expanding that zone,” said Brown.

With the population still highly vulnerable at about 400 animals, and only seven calves born this year, there is a sense of urgency in figuring out how humans and right whales can share the gulf.

“The groundwork was laid 20 year ago in the Bay of Fundy and we have a long track record of working with all the stakeholders to find solutions.”

RELATED: