The rise of racism across Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic is prompting questions about what constitutes a hate crime and what role the police can play when responding to reports of racism.

According to a Statistics Canada survey, about 20 per cent of participants from visible minorities report more frequent harassment or attacks based on race, ethnicity, or skin colour since the start of the pandemic.

The survey, which was released in early July, included responses from 43,000 Canadians and is part of the agency’s series on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Halifax, a man, who appears to be white, told taxi driver Kuldip Dhunna to go back to his country in a rant that was captured by Dhunna’s dash cam early this month. The rant, which also included a racial slur, came after Dhunna asked the man to wear a mask the next time he takes a cab.

Dhunna was hurt by the man’s actions, but he said the police officer’s initial response when he reported what happened was more distressing.

“He said, ‘you’re a good citizen, you’re Canadian.’ He said, ‘you just ignore him,’” Dhunna told The Chronicle Herald.

The police officer later came and spoke to the two men. Still, Dhunna couldn’t sleep that night thinking of the officer’s request to ignore the other man.

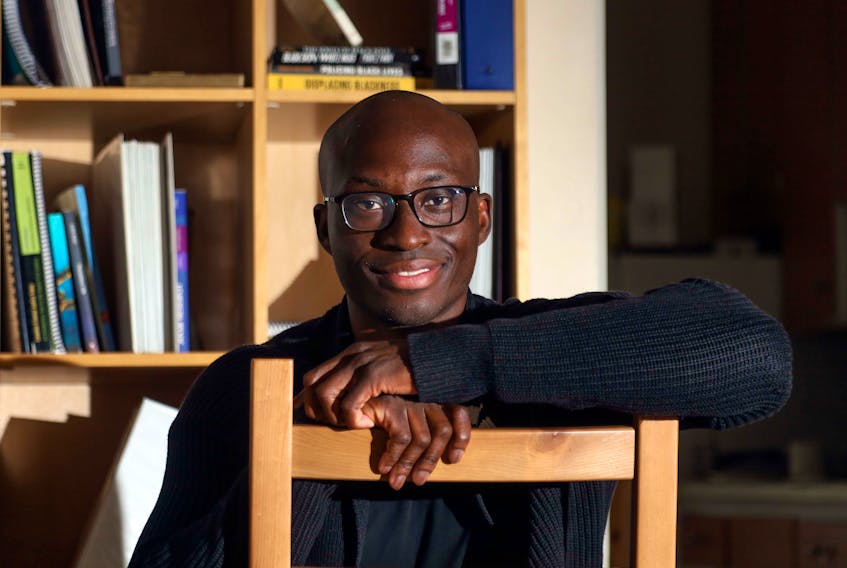

“One of the problems with that kind of approach is there’s more at stake than this individual incident,” said Timothy Bryan, a sociology professor at Dalhousie University who studies the policing of hate crime.

When police don’t take hate seriously, whole communities may start having issues trusting the police. This is especially true for Black, Indigenous, people of colour and newcomers who may have historically been targeted by police.

“You don't want people to have to choose between police and just putting up with violence,” said Bryan. “The effect may be that the public won’t report to police at all.”

Bryan said police need to convey to the public that these incidents are important and that they should be reported whether they were crimes or not.

“They're serious matters period,” he said. “They affect one's ability to live comfortably in one's community. … It affects one's feelings of safety.”

What is a hate crime?

Bryan defined a hate crime as a criminal act that has been committed against another person or property, in whole or in part based on the person’s perceived identity or the location’s perceived connection to an identifiable group.

It can be motivated by a person’s colour, race, religion, national or ethnic origin, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or mental or physical disability.

While the investigation into the racist incident Dhunna endured revealed no criminal offence, Dhunna and his daughter were puzzled that the man’s behaviour had no legal repercussions.

But that’s the reality for many racist acts.

“From the police perspective, what they’re looking at is whether a crime was committed,” said Bryan.

There are few sections of the Canadian Criminal Code that speak to crimes motivated by hate.

Section 318 of the criminal code states it an offence to advocate or promote genocide. Section 319 forbids the public incitement or wilful promotion of hatred. Section 320 deals with print materials that are believed to be hate propaganda.

Bryan said the three sections are often used in situations associated with the spread of divisive or hateful ideologies, such as distributing pamphlets or organizing rallies.

“The threshold for conviction is quite high,” he said. “In some jurisdictions, they actually require the approval of the attorney general in order to even lay the charge.”

Damaging or interfering with a religious property that is motivated by hate is also considered a crime, according to Section 430.

If another crime of any nature is motivated by bias, prejudice or hate, then Section 718.2 allows for the judge at the time of sentencing to consider hate as an aggravating factor.

“So, they could increase the sentence just because the crime was motivated by hate,” said Bryan

Most racist acts, including what Dhunna experienced, are considered hate incidents.

Hate incidents are activities that are not accounted for in the Criminal Code. So, a police officer can’t charge a person committing these activities with an offence.

“It may be racial slurs. It may be gestures,” he said. “These kinds of behaviours get normalized to such an extent that they don't even get reported and that's the danger.”

A deliberate strategy

The problem also arises when police don’t consider the consequences these behaviours could have on public safety.

That’s because not investigating these cases makes offenders believe they can get away with their behaviour, causing them to repeat it. Ignoring a report could also lead to potential criminal conflict that might arise from the racist incident, such as assault.

So, police should start by investigating any report of a hate incident even if it wasn’t criminal.

There should also be a formal mechanism of documenting and tracking these reports, so the police don't miss any linked incidents.

At the time of the racist rant experienced by Dhunna, Const. John MacLeod, Halifax Regional Police spokesman, told The Chronicle Herald that he encourages people to report racism to police.

But Bryan said that’s not enough.

“Urging the public to report only matters if the report actually matters,” said Bryan. “If the public reports and the response they get after reporting is this is not a police matter, then why would they report?”

Police need to have a deliberate strategy to encourage reporting hate-motivated incidents, said Bryan.

It includes providing education to people about what hate crime is, what it might look like and what they should do about it. Bryan said there’s also an opportunity for a broad approach where this message is reinforced in places such as schools and universities.

“When you don't do that you underestimate the impact that these kinds of acts have on people. In many cases it's terrifying. It's humiliating,” he said.

Nebal Snan is a local journalism initiative reporter, a position funded by the federal government.