Lionel Desmond did not share everything with those tasked to help him.

The darkest reaches of his thoughts were kept hidden behind the friendly, conscientious disposition he presented to mental health staff, like the family doctor in New Brunswick, who had signed a form encouraging the Afghan War veteran be allowed to have a firearm and acquisition licence; emergency room doctor Justin Clark, who saw Desmond when he showed up at the St. Martha’s Regional Hospital emergency room on Jan. 1, 2017; and Dr. Faisal Rahman, a psychiatrist who didn’t see a man he thought was about to commit a heinous act of violence against the females in his life.

The fatality inquiry, which is being held in the Guysborough Municipal Building, will never get to ask Desmond whether he saw this man in himself.

Desmond left few clues. There’s his Facebook profile, which still exists, titled Lionel Demon, which also states, “I’m nice, polite but I speak my mind.” There was the “significant planning” required by Desmond to conduct the raid on his home as noted by the lead investigator for Northeast Nova major crimes noted during his testimony last week.

There were the 90-plus searches for firearms on his cellphone after his wife, Shanna, asked him to leave their Upper Big Tracadie home after an outburst on Jan. 1, 2017. He didn’t admit those when he told Rahman he didn’t have access to a firearm in the family room of St. Martha’s Regional Hospital emergency department that evening.

In that room, 46 hours before the triple murder-suicide, was a frontline soldier from the war in Afghanistan who had become well acquainted with the questions and expectations of mental health professionals.

Across from him was a psychiatrist whose early career was spent learning and treating the symptoms and struggles of war veterans.

The chief of psychiatry for everywhere east of the Pictou County line (including Cape Breton) saw 15-20 suicidal people a week at St. Martha’s. He regularly saw veterans, RCMP officers, paramedics and other first responders suffering, as Desmond did, from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Psychiatric assessment

After getting a call at about 7:30 p.m. on his cellphone from the emergency room doctor about Desmond, Rahman took a few minutes to do a quick scan over a psychiatric assessment performed by psychiatrist Dr. Ian Slayter a month earlier.

That included diagnoses for major depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, post-traumatic brain disorder, borderline delusions regarding his wife and possible attention deficit disorder. It placed Desmond’s suicide risk as low.

“I would normally see someone with PTSD just once only to confirm the diagnoses and make recommendations . . . ,” Slayter's report concluded.

“However, given (the) complexity of his case and given that he seems to be falling through cracks in terms of follow up by military and veterans programs I said I would follow him for a short while to help him get connected.”

Rahman began with broad questions: What brought you here? How can we help you?

Desmond told him he was there because he'd had a fight with his wife that began after he put their truck in the ditch on New Year’s Eve. He’d pounded a table that morning in anger, startling their 10-year-old daughter Aaliyah and his wife had asked him to leave. He felt really bad about it.

He wanted a place to stay for the night and he’d go back home the morning.

Desmond told the psychiatrist there was no need to call Shanna.

Rahman dug deeper into the relationship.

“It appeared to be more of an interpersonal conflict but not necessarily related to PTSD,” he testified on Tuesday. “This was a longstanding conflict.”

Desmond showed some bitterness.

He said he’d paid for Shanna’s tuition to nursing school at St. Francis Xavier University and that now she was working he didn’t see any of the money. He said he’d kept the receipts for the tuition – as he would do two days later for an assault rifle.

But he brightened when asked about Aaliyah. He told Rahman he was a proud father who had provided for his family.

Through the conversation, Rahman was sizing him up.

“As psychiatrists, we don’t have medical tests of blood work or lab work (to verify what patients tell us). We rely on interviews and patient self-reporting."

- Dr. Faisal Rahman

“Very pleasant, engaging, maintained good eye contact, appropriate, forthcoming, calm and composed, good hygiene, good demeanour, good grooming,” Rahman listed his impressions of Desmond.

The psychiatrist was also looking at the risk factors.

“Male gender is a risk factor, having PTSD, being in interpersonal conflict, a past suicidal attempt or suicidal gesture,” testified Rahman.

But Desmond had a diagnosis and a treatment plan. He had been seeing a Veterans Affairs social worker and a therapist. He promised to make a follow-up appointment with Slayter.

He did not appear to meet the requirements for forced admission under the Involuntary Psychiatric Treatment Act.

Desmond was, after all, admitting himself.

Without an apparent medical requirement to spend the night in hospital, Rahman made a social admission – a common practice outside of Halifax to help people with nowhere else to stay the night.

Desmond said Shanna had begun working on the mental health ward and asked if there was some other place in the hospital he could stay. So Rahman placed him in the emergency room’s observation ward – a room with six beds separated by curtains and its own dedicated nurses.

The next morning, Rahman met with Desmond again, asked if he’d stay another night so he could meet with a social worker the following day.

But Desmond wanted to go.

'I was devastated'

He spent the day, Jan. 2, moving his possessions to the house of a family friend where he had been offered a place to stay.

On Jan. 3 Desmond returned to the hospital to make an appointment as promised with Slayter for later in the month.

That afternoon he legally purchased a Soviet-era assault rifle at Leaves and Limbs in Antigonish, changed into heavy camouflage clothing, parked a kilometre away from his Upper Big Tracadie home on a woods road, snuck up to the back of the home via a path, slashed two tires on Shanna’s truck, then opened the door to the double-wide trailer and went inside.

This Lionel Desmond doesn’t appear in the medical records presented so far at the inquiry.

Whether Shanna knew this Lionel Desmond, we may never know, though she had previously told a doctor that she wasn’t afraid of him.

On Jan. 4, Rahman was in the admissions room of St. Martha’s Hospital when news came in of the murder-suicide.

“I was devastated,” said Rahman.

Asked if the new boxes to check on the revised risk assessment tool for psychiatrists that came out after the tragedy would have caused Desmond to be held at the hospital or treated differently, Rahman said, “I don’t think so. … As psychiatrists, we don’t have medical tests of blood work or lab work (to verify what patients tell us). We rely on interviews and patient self-reporting. Given the whole circumstance I had no grounds to keep him in hospital on an involuntary basis.”

RELATED:

- Desmond calm, polite during ER visit two days before killings, doctor testifies

- RCMP officer describes grim scene at Desmond home to fatality inquiry

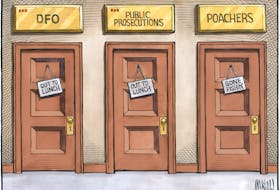

- 'Systemic failures' led to tragedy, Desmond inquiry told

- Desmond inquiry adjourned until January

- Family of Desmond murder-suicide victims can’t escape crime scene

- Inquiry will delve into Lionel Desmond's deadly actions

- GAIL LETHBRIDGE: Inquiry should broaden scope, delve into PTSD

- Deaths in Upper Big Tracadie leave relatives, community shocked