In a picture on display at the Dartmouth Heritage Museum, Frank Baker sports a sailor’s uniform, and, with some friends, is seated somewhere leafy in the City of Lakes.

An old box camera lies on his lap. A wooden tennis racket leans beside the Broughton, England-born butcher-turned-British Royal Navy sailor.

I don’t know when the picture was taken, but if it happened after Dec. 6, 1917, I wouldn’t be at all surprised.

In that photo Baker’s handsome face bears a mighty melancholy expression for a young man on a summer tennis outing. It was as if he had seen something unforgettable, which he surely had.

Baker, according to the exhibit at the Dartmouth museum, had served mainly in the North Atlantic during the First World War.

In 1917, though, he was stationed in Halifax, where he served on the examination vessel Berthier. That December he was transferred to the CSS Acadia — a hydrographical mapping vessel which had been transformed into a coastal patrol ship — where his job was to check ships entering Halifax harbour for spies and smuggled cargo.

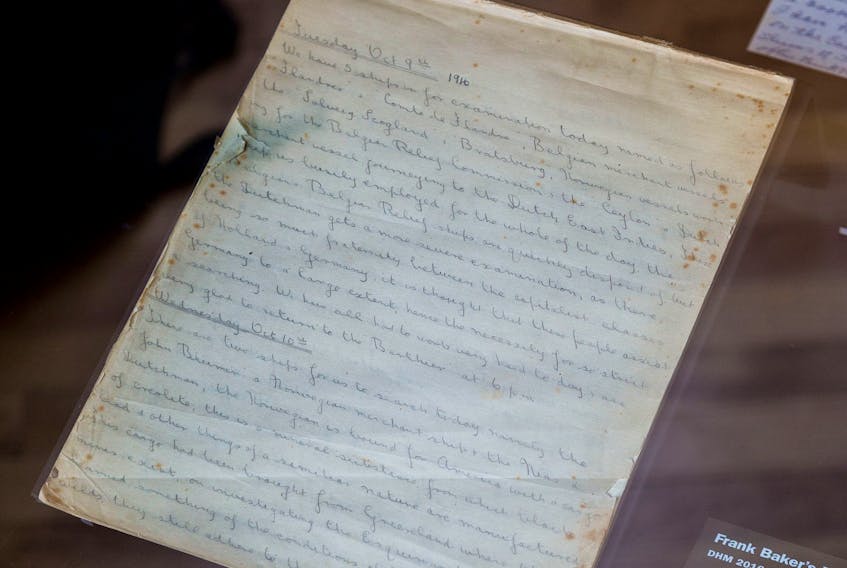

December the sixth began normally enough, according to Baker’s diary, which has been donated to the museum by a son who lives in Australia.

He rose at 6:30 a.m., and got to work with the usual seaman’s chores until breaking for breakfast at eight. Afterwards, there were no ships in the harbour for examination.

“So we again proceeded to cleaning stations and had just drawn soap and powder and the necessary utensils for cleaning paint work,” Baker wrote in clear cursive, “when the most awful explosion I ever heard or want to hear again occurred.”

The first thud, he wrote, shook the ship from stem to stern, the second threw some of the crew under the gun carriage and others “flying in all directions all over the deck.”

Fearing an attack by enemy submarines they made for the upper deck. There they saw a “veritable mountain of smoke of a yellowish hue.” Huge pieces of iron flew all around them.

“A shower of shrapnel passed over the forecastle shattering the glass in the engine room and chart room to smithereens which came smashing down into the alleyways.”

Baker wrote that it was the “greatest miracle in the world” that they didn’t all die from the falling debris, the fires that broke out below decks, and the sheer power of the explosion that ripped the side out of a nearby tug, injuring several crew members, including one who had a piece of flesh “weighing nearly two pounds” torn out of his leg.

When the smoke finally cleared they saw what had happened: the Mont Blanc, a French-owned freighter loaded to the gunnels with TNT had collided in the harbour narrows with the Imo, a Belgian relief ship, triggering the largest manmade explosion in history until the detonation of the atomic bomb.

Baker’s eyewitness account of the disaster, which occurred 102 years ago on Friday, makes for hard reading.

The side of one of the ships had been thrown 365 metres away. Hundreds of small crafts had been “blown to hell.” Ships that only hours before had been beautiful vessels were reduced to total wrecks. The harbour “presented an awful scene of debris and wreckage” he wrote, with dead bodies “lying battered and smashed all around.”

Baker and his crewmates went ashore to briefly visit a devastated hospital, then returned to the Acadia, to resume their duties guarding the harbour. At one point they helped to bring order to a ship whose crew had mutinied.

Then, after a “hurried tea” they went ashore where Baker witnessed a scene that he described in his diary as “utterly indescribable,' which did not stop him from trying to do so.

“The town was literally ablaze,” he wrote, “the dry-dock and dockyard buildings completely demolished and everywhere wounded and dead.”

Little children, searching for their dead parents were “crying piteously,' while their relatives inquired for their loved ones as the military tried to keep order in the devastated streets.

Wandering through the carnage, he and his crewmates found themselves in one of the most-ablaze parts of the city. Again, you can sense the disbelief about what he is seeing.

“It is beyond me to describe the absolute terror of the situation,” he wrote, “for miles around nothing but a flaming inferno, charred bodies being dragged from the debris, those

poor devils where life still lingered … piled into wagons and conveyed to one of the improvised hospitals.”

When they returned for their late night shift, I’m assuming aboard the Acadia, Baker wrote about being “sick at heart” over the misery “with which the city abounded.”

At that point, I imagine him gazing back towards Halifax where the glow from stillburning fires was “lighting the harbour up like day.' Then I see Baker, turn his face, surely covered with soot, back towards “the little city of Dartmouth” which was also “aflame on sea and land” where there was only “misery, death and destruction.”

We don’t know exactly what was going through his mind and soul at that moment.

We just know what he wrote when he sat down at his diary — “Looking out on the flaming city from our ship I cannot help but marvel we escaped sharing the fate of thousands of souls in this terrible catastrophe”— and the terrible power of what he experienced can still be glimpsed in the eyes of a man in a photograph a century later.