People often think of poetry as lofty, apart from the real world: ruminations on daffodils or whatever the heck. But poetry is an artform written in real time, current, and even urgent.

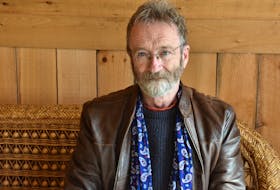

Douglas Walbourne-Gough’s “Crow Gulch” is geographically pegged from the start, opening with a quote from Percy Janes’ “House of Hate” — “There was also Shacktown, a section of the west side where the very poor lived, and beyond that Crow Gulch which was the dumping ground for bums, bootleggers, and other less mentionable outcasts.”

This site infuses the texts.

Originally a migrant settlement for construction workers on Corner Brook’s pulp and paper mill, Crow Gulch was long considered an urban blight and razed in the 1970s. Its environment formed those who lived there.

In “Breaking Ground,” Walbourne-Gough asks “What if the land you want to break is bedrock? / Bald fields of stone flowered with boulders, kissed / by bog and moss less than knee-deep? What if / this land is so stubborn, so resistant to charms / that spruce grow sideways, grown themselves / into knots for spite? … Well, you buck up. / You defy law and logic, squat in tickles and coves, / learn their rhythms, make do along the edges.”

Crow Gulch itself was bisected by the railway. “The tracks were also road, sidewalk / and driveway, nothing to see a few young / fellas hanging off the back / hitching a ride / to Broadway. Over time the racket and rumble / became ingrained in daily life, / a train’s passing / became like the sun – brilliant and mundane / in the same go, able to destroy what / you know at a moment’s notice.”

Crow Gulch was also identified as Indigenous, by outsiders if not by its inhabitants. Exploring this then highly-negative stereotype, Walbourne-Gough includes a miscellany of “definitions” of “jackatar,” such as “they are a lazy, indolent people, and I am told, addicted to thieving …”

The poems are also intercut with short interviews as well as found texts, like as a series of bureaucratic missives assessing Crow Gulch and tracking its fate.

Much of the material is keenly personal to Walbourne-Gough and the words are filtered through the tint of his own memory, like “the odd Steve Miller band / T- shirt” or “the new cashier / with the Pat Benatar haircut”: “Something about the colour of things, / then. Something mono, something VHS, / AM radio about it all concerning aspect / ratios. Pre-pixel.”

Not all of this recall though is benign. In “Interventions,” “A Sunday afternoon spent visiting friends, crawling out of a / three-week hole that’s stretched out for two months … Offered mixed advice – should is a / dangerous word, stop telling yourself the same stories …”

Throughout, Walbourne-Gough is so aware of and precise with words. (In just one possible example, the sun is “patient / as a gunslinger.”) He disinters the houses, neighbours, and family from their scrapped, shunted-aside history, while reimaging and releasing his own past. “Crow Gulch” is superb.

“Inquiries,” by Michelle Porter

This collection, too, unfolds into a map of self and place, as Michelle Porter navigates both her complex Métis-European family lineages and her relocation through various cities and rental properties. As she questions and probes, Porter flexes different formats, such as the pulsing undulating repetition of “Of the Red,” or the XVI-part series “Mama’s Kitchen,” or compositions of solid blocks of texts, or beads of words or phrasing.

Some pieces are distinctly local, like “Colonial Street, 2010” where “The roof leaked. / Hell, the walls / leaked when wind blew the rain / sideways. / Just the way roofs are / in Newfoundland, / said her landlady. Just / the way it is.” Or “Tessier Place, 2012-2014,” where Porter and her family (including two young daughters) lived next door to a notorious drug house that became a scene of a murder.

Frequently she draws a lot from domestic settings and details. “Slicing Lemons in April” builds on “Talk about moving away while a blizzard moves in. He chops sausage / and they try on plans: Back to Alberta? Maybe Manitoba, / where her people are from? Spicy chorizo in a cast-iron pan. Onions in hot oil / and the sharp scent of Spanish spice. BC is too much, isn’t it? / Too expensive for them, right?”

Moving house, and negotiating the ensuing accompanying baggage that activity requires, is a consistent theme. In “Packing Boxes and Loading the Truck,” she asserts “I will not carry your grief on my hip, will not / wet this husk of guilt because the time has come / to leave. I will be your homecoming, here, there.”

“Inquiries” is a lyrical interrogation of the notions of belonging, family, and home.

Joan Sullivan is editor of Newfoundland Quarterly magazine. She reviews both fiction and non-fiction for The Telegram.

RELATED: