Object Lessons of a Pandemic is a new series looking at the COVID-19 pandemic through the history and meaning of the objects that surround it — all the strange, ordinary and essential things that the rise of coronavirus has made us think about in new and unexpected ways. From everyday household items to inventions that have become indispensable, these are the objects COVID-19 will be remembered by.

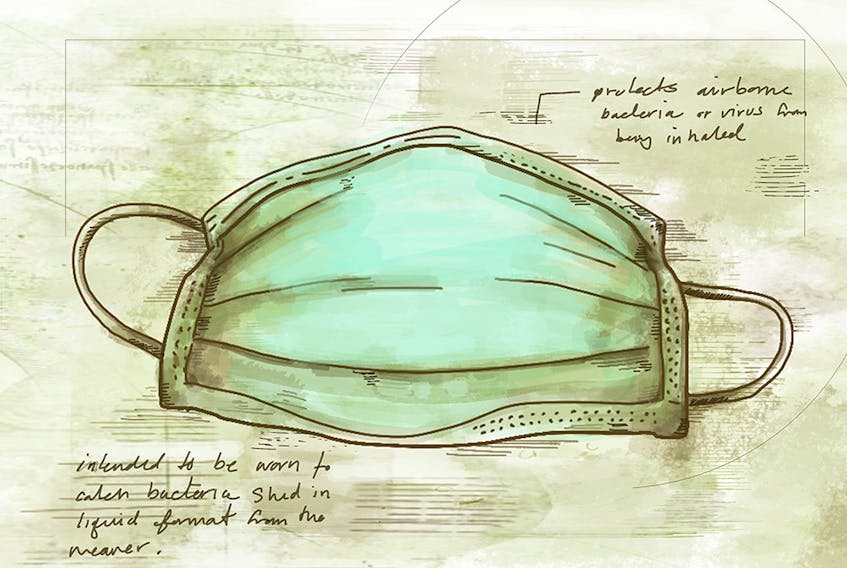

Of the many controversies to emerge during the coronavirus pandemic, the strangest surrounds the use of face masks. As a simple precautionary measure, wearing some kind of face covering, whether a common surgical mask, bandana or scarf, seemed like a sensible recourse for the general public, who started donning them outdoors as it became clear that people were getting sick.

But as COVID-19 hit North America, the public-health messaging around masks was confusing. On Twitter, the U.S. Surgeon General exhorted Americans, in bold all caps, to “STOP BUYING MASKS,” insisting that they “are NOT effective” at preventing the spread of the disease. Both the Center for Disease Control and the World Health Organization seemed to agree, advising against the use of masks except in the treatment of someone who was sick.

But are masks actually effective? It soon transpired that we don’t really know.

In the Atlantic, Ed Yong reports that the evidence “is all over the place,” particularly for the more commonplace surgical mask, which doesn’t form a tight enough seal over the infection-prone parts of the face. (The more elaborate N95 respirators are drastically better-suited to the job, and because they are more expensive and precious, they’ve been reserved mainly for health-care professionals and front-line workers who are the most at risk.) As far as we can tell, COVID-19 spreads through droplets expelled from the nose and mouth. Masks might protect you from some of those droplets, but because they don’t offer a perfect seal, the droplets can still get in from the sides or wherever else there happens to be room.

And yet despite the inconclusive evidence, the popular sentiment began to shift in the opposite direction, and the CDC is now recommending all Americans wear masks outdoors after all. This is in part because masks are effective at helping to prevent the spread of illness when the wearer is ill — even if the masks can’t keep coronavirus out, they might keep it in.

But masks might also serve a critical symbolic function, one that already prevails across Asia, where wearing masks has long been cultural norm. Masks, Yong writes, are “an affirmation of civic-mindedness;” wearing masks “could signal that society is taking the pandemic threat seriously,” and their widespread adoption here could both reduce the stigma of illness and curb some of the racial connotations that have provoked COVID-born xenophobia.

There is still so much we don’t know about COVID-19: exactly how it spreads, how much of it is needed to infect, how long it remains infectious on surfaces or in the air. And, of course, the people who require masks the most — the extremely vulnerable men and women in the health-care sector doing their best to contend with COVID every day; professionals across fields considered essential who are out there in the public; and anyone without the privilege of working from home and self-isolating — are struggling to find it, exactly because the demand for masks has outpaced limited supplies.

Copyright Postmedia Network Inc., 2020