Everyone wants the virus that causes COVID-19 to be a one-and-done. But reports from South Korea are raising the possibility that infections can be “reactivated,” or that the infected, once recovered, could be infected anew.

At least 110 people in South Korea have tested positive for the pandemic virus after having been thought “cured,” according to reports. The World Health Organization told Reuters on Saturday the agency is “working hard to get information” on the cases.

It’s believed the virus may have “reactivated” in some people, as opposed to them being re-infected all over again, or that repeat testing may simply be picking up harmless fragments of virus genetic material that can linger for weeks or months after a person recovers.

It could also come down to nothing more than faulty testing.

There are many different hypotheses

Canadian health officials are trying to verify the information from South Korea. “I think there are many different hypotheses,” Dr. Theresa Tam, Canada’s chief public health officer, said Monday. Tam said it’s important to get “our international partners to expand more on what is actually happening and maybe, yes, having an international collaboration in terms of looking at what happens to someone who has initially been infected.

“We actually don’t know if a test positive means that there is any viable virus in that particular person. That’s one of the first questions to actually answer,” Tam said.

But the mystery cases illustrate just how little is known about the virus — “how the human body actually mounts an immunity and what actually happens in the longer term,” Tam said. That could hamper the herculean efforts being poured into developing vaccines and, in the absence of a vaccine, make natural herd immunity harder to achieve.

Reports from Seoul describe people who tested negative for COVID-19 using PCR (polymerase chain reaction) testing who, some days later, tested positive again.

According to top U.S. infectious disease expert Dr. Anthony Fauci, advisor to the U.S. presidential COVID-19 task force, how long immunity lasts remains unknown. However, in an interview with the editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association, Fauci said the virus isn’t changing much, and that the working assumption, although there is not 100 per cent certainty, is that “if we get infected in February or March and recover, that next September, October, the person who’s infected, I believe, is going to be protected.”

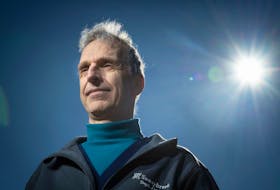

While most people in the medical and scientific community share that thinking, “we’d be foolish to think we know everything about this virus, given that we have only known about its existence for about four months,” cautioned Dr. Isaac Bogoch, an infectious diseases physician and scientist with the Toronto General Hospital.

What proportion of people get immunity, to what extent do they have immunity, and how long immunity lasts are still unanswered questions, Bogoch said. “When we hear about people being reinfected it obviously raises a few red flags.”

Bogoch believes that the most likely explanation is that the recovered patients tested positive using PCR (polymerase chain reaction) testing, which detects viral RNA, because they still carry some residual virus in the areas being swabbed, typically the back of the nose and throat. It doesn’t mean they’re contagious to others, or that the viral fragments are capable of causing disease. The test may be positive for days, even weeks after people have recovered from an infection.

Another possibility is that some people who were initially told they were positive weren’t positive, but then became positive. “And of course, the third possibility that we really hope is unlikely is that there is either reinfection or reactivation of the virus,” Bogoch said. “Obviously, we hope that’s an unlikely scenario. But I think it still warrants exploration.”

With reactivation, the virus triggers another eruption, the way the virus that initially causes chicken pox, varicella zoster, can come back years later as shingles.

“I think these are remote, but not impossible scenarios,” Bogoch said. Given that the virus is so new to humans, “we should at least be open-minded to other possibilities,” he said.

Dr. Anand Kumar, a critical care doctor at Winnipeg Health Sciences Centre, said PCR tests have a certain sensitivity. Some viruses, like herpes, can get inside cells, go into a latent phase and then pop out again under stress. But coronavirus isn’t known to be one of them.

True reinfection is possible, Kumar said. “But they don’t say the amount of time between the (South Koreans) being cleared and the time they became positive again.”

Without seeing any kind of academic paper, the idea of people bouncing back from negative to positive would likely come down to a testing issue, added Dr. Mark Loeb, a professor of pathology and molecular medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton.

“If someone has had a natural infection, it’s likely that they would be immune, at least in the short term,” Loeb said. “It’s not proven, though. We’re dealing with likelihoods right now. Is it likely? I think it’s likely. Is it certain? No.”

• Email: [email protected] | Twitter: sharon_kirkey

Copyright Postmedia Network Inc., 2020