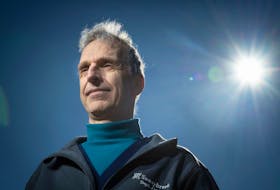

Just how great a risk or not COVID-19 is in classrooms has an entire nation slightly unnerved, so mathematician Chris Bauch and his collaborators decided to plug some scenarios into a model.

Their projections? Class sizes of the magnitude many provinces are allowing could lead to outbreaks lasting weeks or even months.

The number of infections increased rapidly with the number of children in a primary school classroom or before-and-after school daycare program, according to the model. “As you double the class size, from eight to 15 to 30, the number of cases and also the lost student days of instruction not only double each time, they triple or quadruple or quintuple,” said Bauch, a professor of mathematics at Waterloo University and lead researcher on the study . “Those losses accelerate as you go to larger and larger classes.”

Policy makers planning for elementary school class sizes of 30 kids or more “need to immediately reconfigure their school opening plans” and switch to hybrid models of part in-person, part online, he said.

Teachers in B.C., Alberta, Quebec and Ontario are demanding smaller class sizes. Ontario’s plan has students in kindergarten through Grade 8 returning to school without any reduction in class sizes, though they’ll spend the day in a single group to limit contact with other children. Ontario Premier Doug Ford has insisted the plan is based on expert advice.

“Our plan to safely reopen schools has been informed by the best medical and scientific minds in the country,” Caitlin Clark, a spokesperson for Ontario Education Minister Stephen Lecce, said in an emailed statement.

“The evidence is emerging, and our plan is a living document — it’s meant to be augmented and adapted to apply the best advice as it emerges. The leading medical advice was clear that we must allow an opportunity for our students to return to school,” she said. “We recognize that school boards have developed plans that best suit their local needs. We will never hesitate from taking further action to protect the health and safety of Ontario’s students and education staff.”

Outbreaks in schools are already happening. Israel began to see major outbreaks of COVID-19 in high schools weeks after reopening in May. On Friday, the Associated Press confirmed reports that hundreds of students and teachers at dozens of schools in Berlin have become infected with the coronavirus and are now in quarantine, less than two weeks after schools reopened.

The new modelling study, which hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed, was designed to capture transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes the dreaded COVID-19. Researchers looked at the effect of different student-to-teacher ratios in a hypothetical primary school, as well as school-based daycare, an essential “bridge” for working parents who can’t drop-off or pick-up kids around the school hours.

Under their most optimistic scenario of masking, social distancing and good hand washing, the model predicted an average of 53 infections during an outbreak in a school community of 150 students, parents and teachers in classes of 30 students, versus 12 infections for classes of 15, where students attend alternative weeks in groups of 15 each.

Outbreaks happened over 40 to 60 days, on average, for the 30-students-to-one-teacher ratio. The number of student-days lost due to classroom closures ranged from 75 for the smallest ratio, to 1,000 for the largest. “Student days are like passenger miles — it’s the number of students affected, times number of days lost,” Bauch said.

School is going to accelerate spread of the virus if it's already in the community

The model is based on assumptions, including the infectiousness of the virus and how quickly it can spread. It assumed children and teachers are at a “constant background risk of infection from other sources,” like shopping centres. But Bauch explained the math as a “triple whammy.”

“When you put more students in a classroom there is a higher chance one of them will test positive at some point for COVID, and so you’ve got to close that classroom.” The larger the class, the more students affected at a time. But because people can spread COVID before they develop symptoms, “by the time you’ve identified that COVID case there might be other cases in the classroom already,” Bauch said. And, the more kids in a classroom, the trickier the social distancing. “You get aerosol transmission and you generate more cases by the time the classroom gets closed,” he said.

“Many people may infect only one person, or even no one, but in some cases you have a so-called super-spreader who infects a huge number of people,” Bauch said.

In Ontario, masks are required for children in Grades 4 to 12 only.

In the model, sometimes the teacher was the first to get infected but usually it was the student, “because there are more of them. They bring it in somehow and we model what happens — where they spread it in their household and where they spread it in school.”

Still, it’s not clear just how efficient children are at spreading the virus that causes COVID-19. Younger children seem less affected by SARS-CoV-2 than adults. But the science doesn’t agree, and most schools have been closed for much of 2020.

“School is going to accelerate spread of the virus if it’s already in the community,” said Montreal cardiologist and epidemiologist Dr. Chris Labos. “This is the same thing that happened when we reopened stores and restaurants. (School reopening) is not going to create more virus, but it’s going to make it easier for the virus to spread,” he said. “If the number of circulating cases is low you’re probably going to be okay.”

“It’s very possible you could see cases,” Labos said. What’s going to make the difference is testing, contact tracing and isolating infected students and teachers to prevent outbreaks.

The study didn’t take neighbourhood risk and other social determinants of health into consideration. The Toronto District School Board plans to reduce class sizes in elementary schools in neighbourhoods at highest risk of COVID-19.

For childcare, the 15 children to two teachers ratio was universally the worst across all possible scenarios. It showed the quickest start of an outbreak. Childcare should be operating on a seven or eight kids per room model, Bauch said. Siblings should also be grouped together in daycare.

Co-authors of the study included Brendon Phillips, a PhD candidate in Waterloo’s department of applied mathematics, Dillon Browne, an assistant professor in Waterloo’s department of psychology and Madhur Anand, a professor at the University of Guelph.

• Email: [email protected] | Twitter: sharon_kirkey

Copyright Postmedia Network Inc., 2020