DARTMOUTH, N.S. — Editor's note: In the interest of personal privacy, the patient's name has been changed for this article.

Standing before the seven-foot-tall steel machine, Charlie taps the touchscreen. The scanner lights up. He holds his palm a couple inches from the scanner. It flashes. Shining an invisible infrared light through his skin, it recognizes the veins in his palm. His profile is already in the server as an opioid addiction patient.

A doctor watches beside him. A documentary film crew points their camera. Corey Yantha, one of the people responsible for the machine, is also watching nervously from the corner of the room.

The scanner beeps. Charlie reaches in to the dispensing basket and takes out a small bag containing pills. A timer pops up on the screen, showing how long it will be until the next dose is available.

Charlie's bag holds vitamin D pills, not opiates. He's helping test the machine.

It works. The quick, easy transaction belies the long, hard work it took for the machine to end up at its spot on Hastings Street in Vancouver, the sick heart of Canada's opioid crisis.

Biometric technologies

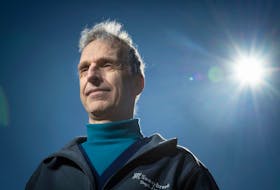

The successful testing was bittersweet for Yantha, co-founder of Dispension Industries.

“It's exciting, but it's not an exciting thing,” he says of seeing his machine deliver faux opioid pills to a patient. He wasn't expecting his business to be drawn into a health care catastrophe.

Yantha co-founded Dispension Industries, proudly based in Dartmouth, in October 2017 with four other people, including Ryan Smith and Matt Michaelis. Yantha and his peers wanted to get involved in the soon-to-be-legal cannabis industry but didn't want to compete with growers.

Happening on the idea of a cannabis vending machine, they knew it needed to be capable of identifying users who were of age.

“We started to identify biometric technologies,” says Yantha.

Eyeball scanning was too discomforting. Facial recognition felt like your identity might be stolen. Fingerprint scanners malfunctioned too easily. Infrared vein-scanning technology seemed just right: no need to touch anything, not too personal and it's dependable. The veins inside your palm are as unique as your fingerprint.

Dispension is now filling orders for the 800-pound steel machines that can be customized to sell just about anything regulated.

“We've included a whole metal plate” behind the screen, says Yantha, so thieves can't bash their way in.

“There's CCTV, there's internal and external alarms, a shatter-resistant screen,” he says.

Twenty machines will soon ship to the Caribbean to dispense medicinal cannabis.

Dispension wants to deploy its machine in Canada.

“There's been a lot of regulatory work” proving the company's “verified identity dispenser” is more than just a vending machine, says Yantha.

Laws that prohibit vending machines from selling controlled substances stand in the way.

Opiate crisis

Amidst that work, Yantha read an article about a Vancouver doctor who made headlines declaring that tainted street opiates were killing so many people, vending machines dispensing clean drugs were the solution.

Yantha contacted Dr. Mark Tyndall.

“When he called me, I said, ‘wow, I didn't even know that would be possible, so let's talk,'” remembers Dr. Tyndall, speaking by phone from Vancouver.

Tyndall, a public health expert and former executive directer of the BC branch of the Centre for Disease Control, has watched the opioid crisis get unfathomably dire in less than five years. “Things started getting off the rails around 2016. At that time, we didn't really understand why overdoses were going up so quickly,” he explains.

According to the City of Vancouver's website, BC's overdose crisis was declared a public health emergency on April 14, 2016. Since then, there have been over 3,600 deaths. The overdose death rate in Vancouver has increased every year since, and it continues to break records.

“This is really a poisoning epidemic…the whole drug supply has now been contaminated,” says Tyndall.

Every batch of street drugs has a new recipe, often containing fentanyl or carfentanyl. They are more toxic than ever.

Dispensing machines will remove the risk of unknown street drugs, and patients won't have to resort to crime to make enough money for their next hit.

Yantha travelled to Vancouver recently to set up the first machine. Conditions there were “horrific,” he says. Firetrucks, ambulances and police cars were “racing up and down the street” responding to overdoses.

After about a week, testing was underway.

By 2020, Charlie will be standing in front of the machine again. He will go through the same motions, only this time, nobody will be looking over his shoulder. He will walk away from the machine with a clean, pharmaceutical-grade opiate.

The Dartmouth boys at Dispension are happy the machine might help prevent overdose deaths and are hoping to see Dr. Tyndall's plan succeed and expand.

“We're just enabling a solution with our technology,” says Yantha. “It's not about us.”

HOW IT WORKS

- The client steps to the Verified Identity Dispenser and touches the screen to activate the scanner.

- The client holds their hand two or three inches from the scanner.

- The scanner uses infrared light to see the veins under the skin of the palm.

- The machine looks at about 1,000 different points among the veins. Every person's vein pattern is unique.

- The 1,000-point image is processed into an encrypted binary code, and matched to the patient's file on the server.

- The dispensing basket opens to deliver a specific dose of opiate pills to the patient.

- The dispensing door closes. The screen displays things like locations of nearby safe-injection sites or the weather forecast, in case the patient doesn't have a home.

- The screen displays a timer telling the patient when their next dose is available.