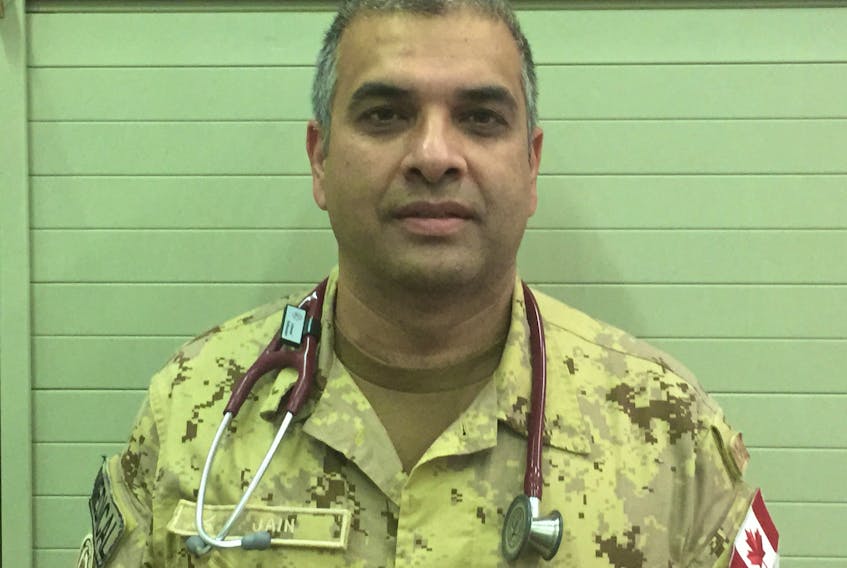

Dr. Trevor Jain had the necessary training to undertake the critical mission he was suddenly thrust into just hours after Swissair Flight 111 plunged into the Atlantic Ocean 10 years ago.

But there could be no possible way to fully brace for the heavy emotional and mental assault that was levelled over his eight-week long grim assignment - a torturous task that has left him with indelible, unsettling memories.

Jain, 38, of Stratford was a fourth- year medical student and a captain in the infantry serving with the West Nova Scotia Regiment when he got the call to action at 3:30 a.m. on Sept. 3, 1998.

Just five hours earlier, the wide-body jet crashed into the dark waters as it tried to land at Halifax airport shortly after the pilots reported smoke in the cockpit.

As ordered, Jain reported to CFB Shearwater, where confusion reigned.

"So when I arrived at the hangars, it was like chaos,'' he recalled in an interview this week with The Guardian, while sitting in a small office at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, where he has been working for the past five weeks as an emergency specialist.

"There was like six different organizations. Nobody really knew what was going on.''

HMCS Preserver, which arrived within an hour of the crash and implemented search and rescue Operation Persistence, informed Jain and others that one body had been recovered, but that there were no survivors among the 229 passengers.

"No matter what type of background, no matter what type of training, it didn't matter, you were affected.''

-Dr. Trevor Jain

Dr. John Butt, Nova Scotia's chief medical officer at the time, ordered Jain to get a morgue up and running in the aircraft hangar - pronto.

Prior to medical school, Jain was a pathology assistant. He knew how to design, set up and run a morgue.

He did not feel besieged by the task at hand, despite the urgency and magnitude of the almost unspeakable operation that had been born from such a horrific event.

"It's funny because it wasn't overwhelming initially,'' he said.

"It was like your training kicks in and you just are like 'OK, this is what I need, this is how I've got to do it' . . . I think it became overwhelming after the operation.''

Jain's job was to command and control the morgue floor. He needed to ensure that all autopsies on the human remains were done correctly.

Four autopsy teams worked 18 hours a day for the first three days. There was, Jain recalls, intense pressure to identify everybody as quickly as possible for political, religious, social and insurance reasons.

Being trained professionals, despite what many in the general public might have thought, did not insulate the people working in the morgue from a daily horror of dealing first hand with such a disturbing spectacle of loss and devastation.

"A pathologist or (emergency doctor) would be used to seeing one or two dead bodies (in a day) but to have 229 people at once that are deceased and every day for six to eight weeks, eight hours to 16 hours a day, you're looking at the human body in all shapes and forms,'' he said, shaking his head over the graphic image.

"No matter what type of background, no matter what type of training, it didn't matter, you were affected.''

In an effort to cope, each person remained in one of the four tight-knit autopsy teams, drawing on one another for the strength to complete their unsavoury assignment.

They worked together and ate together. They were quartered together and they hung out together. Many, said Jain, made a point of not speaking to family members of the victims in an attempt to not be overwhelmed with the tragedy.

Still, the excruciating human side of the disaster was constantly staring Jain and his comrades straight in the face, whether hauling out a wallet that contained a photo of a deceased passenger or handling a severed limb that served as the canvas for a military tattoo. Victims, indeed, were easily humanized.

"...A week after I finished at the morgue, walking down Spring Garden Road in Halifax and I just wanted to tell everybody I was happy they were here...To see life in action: people shopping, drinking coffee, arguing - a lover's spat."

-Dr. Trevor Jain

Jain and the morgue crew even kept a bulletin board with newspaper clippings. Names would appear in articles that would quickly resonate.

He would read, for instance, of parents grieving the loss of their daughter - a person Jain may have hours earlier identified through DNA. That made his job that much more personal.

Sometimes, the work was too personal to bear, a gut blow that simply could not be deflected or cushioned.

He collected DNA on three young children. That task hit him and others hard. One man was unable to pick up his daughter for a number of months.

"He would just see body parts,' said Jain.

"He would pick up his daughter and just look at the leg. I mean it boggles the mind when you think about it."

Jain said everybody involved in the mission - he is one of only six people to receive the Meritorious Services Medal for his role in the recovery operation - has been scarred to some extent.

"There are some people that haven't recovered from that experience,' he said.

Jain, naturally, took his share of blows too.

The nasty routine of his work became so ingrained, Jain found himself mimicking, in his mind at least, that mental dictation he had done time and again during his eight long weeks in the makeshift morgue.

"If I shook someone's hand, I would say, you know, '38-year-old male, brown skin, with a wedding ring,' But that has faded.'

He has still been unable to revisit the crash site off

Peggy's Cove, fearing nightmarish images might cascade over him like a mighty wave.

His harsh memories are intensified each year on the anniversary of the tragedy. He found the 10-year milestone Tuesday was fueled by a bombardment of media accounts.

"And a lot of the memories all came flooding back,' he said.

Despite taking a heavy pounding, Jain has managed to get up off the matt, and on with his life.

He has been given a clean bill of health, mentally and physically, and is eager to see what the future holds for him, his wife Kara, and

their three-year-old twin daughters, Sydney and Natasha.

He loves Prince Edward Island and is "seriously considering putting down roots here.'

His mood today perhaps mirrors that heady feeling he had shortly after completing his grim work in the somber yet hectic confines of a

military hanger turned morgue.

"I remember distinctly, a week after I finished at the morgue, walking down Spring Garden Road in Halifax and I just wanted to tell everybody I was happy they were here...To see life in action: people shopping, drinking coffee, arguing - a lover's spat."

In other words, normalcy?

"Yeah, normalcy. I just wanted to shout 'I'm happy you guys are here, whoever you are.'"