The policy consensus that has guided economic decision-making for decades is being challenged like never before. The Financial Post explores the opportunities and unknown costs in the Great Rethink series.

De-globalization became a buzzword back in March when we were fighting over toilet paper. The answer to shortages of staples, face masks, ventilators and medicine seemed obvious: local production. Sprawling international supply chains had to get shorter. It was a matter of life and death.

Guess what? It’s not happening, at least not in a significant way. “No,” Keith Creel, chief executive of Canadian Pacific Railway Ltd., bluntly said on Oct. 20 when an analyst asked him if CP’s customers were talking about “near-shoring.”

The Bank of Canada has uncovered a similar sentiment. “In the near term, most firms do not expect to pivot away from their existing processes and relationships,” the central bank said in its Business Outlook Survey on Oct. 19. Furthermore, merchandise imports from China averaged $4.27 billion per month between April and August, compared with an average of $3.83 billion over the same period in 2019, according to Statistics Canada data .

Globalization continues apace, meaning international policy is as important as ever. That’s unfortunate, because Canada’s approach to world affairs has rarely looked more tentative and confused. The lack of strategy means the country is setting up to be a follower in a world where more focused nations shape the rules and norms that will govern climate change, security, technological standards, international taxation and trade.

Canada fought with the good guys in the world wars, earned memberships to all the right international clubs, and benefited greatly from a neighbour that was generally happy to buy most of our excess production and handle regional security. But our protective bubble has popped. Geopolitics has gotten real, and we’re probably not ready.

“We have just been incredibly lucky for 50, 60 years,” Jennifer Welsh, director of McGill University’s Centre for International Peace and Security Studies, said on political pollster David Herle’s podcast, The Herle Burly, earlier this month. “It’s made us a little bit lazy. We’ve been incredibly fortunate. And now all of that is crumbling. We can’t take any of that for granted. It requires us to be very clear-eyed about what’s going on.”

One of the reasons that Stephen Harper and Justin Trudeau let international policy slip is that it’s really hard.

Welsh, who previously taught at Oxford University, helped assemble a dozen experts on global affairs earlier this year to get the conversation started. The group came up with a compelling list of 10 “ strategic choices ” that policy-makers need to make, and zero answers. They acknowledged the degree of difficulty, but stressed that Canada’s last attempt at framing an international strategy 20 years ago is now obsolete.

“The global political environment has been so relatively positive and co-operative that at times we have taken it for granted,” Welsh and her counterparts said in their report, published by Global Canada, a non-profit that doles out policy advice. “Today, we do so at our peril.”

It might help to go back to the beginning of the current global order and consider how Canada helped to shape it. That means digging deeper than the North American Free Trade Agreement in the 1990s, the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement in the 1980s, our inclusion in the G7 assembly of rich countries in the 1970s, and the auto pact of the 1960s.

The global political environment has been so relatively positive and co-operative that at times we have taken it for granted. Today, we do so at our peril

It means going back to Bretton Woods, N.H., at the end of the Second World War, where Canada played the role of honest broker between the world’s two most powerful countries during the negotiations that created the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the precursor of the World Trade Organization.

“That’s a very valid starting point,” said Eric Helleiner, a political science professor at the University of Waterloo in Ontario who wrote a history of the Bretton Woods talks. “The Canadian officials played an important role of trying to bridge the competing American and British plans.”

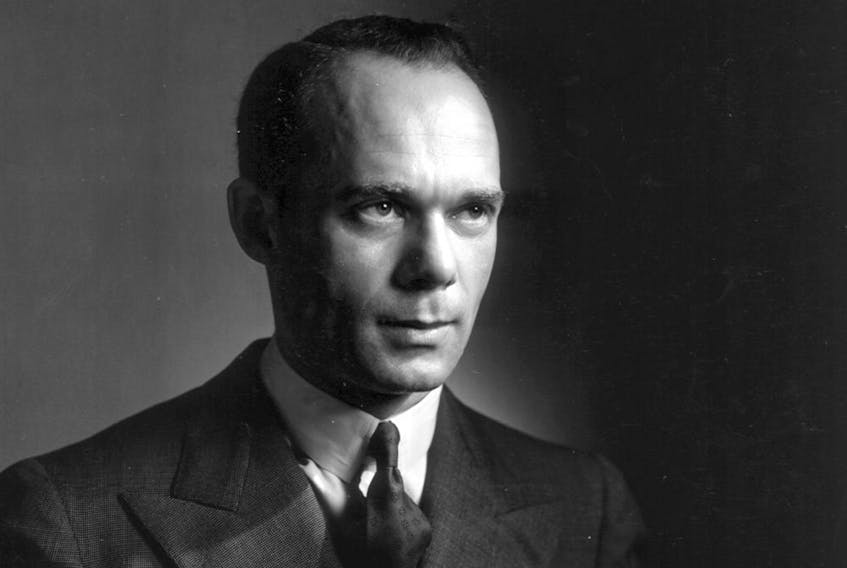

Canada’s negotiating team featured Louis Rasminsky, a future Bank of Canada governor, who held his own against Britain’s John Maynard Keynes, the world’s most famous economist, and Harry Dexter White, the domineering head of the U.S. delegation.

Rasminsky was talented, but he also benefited from a clear vision of how his country wanted to operate in the world. Canada had some selfish goals: its export earnings were primarily in sterling, while the bills for its imports were invoiced in U.S. dollars, so it had a lot riding on the system of fixed-exchange rates that the IMF would oversee.

But, ultimately, Canada wanted an economic order that was as open as possible, as the former British colony realized that American hegemony would be akin to swapping one master for another. Forty-four countries were involved in the talks, but Canada was one of only four that produced counter-proposals to the ones that Keynes and White put on the table.

It was an attempt to both find middle ground and indirectly influence White by swaying public opinion in the U.S., where Canada was seen as a neutral participant, rather than an antagonist.

“The Canadians got very involved in the negotiations,” Helleiner said. “They worried that Canada would be forced to choose between focusing on either the sterling bloc or the U.S. dollar area. That was not an attractive choice, since Canada had important economic ties to both.”

Today, Canada could similarly aim to re-establish itself as an honest broker at any negotiation that threatens to make the world smaller, though that would require putting some distance between itself and Washington.

In the 1940s, Canada would have been an important ally of both the U.S. and Britain; today, Canada is seen as an automatic vote for the American position. We could restore a degree of independence by quitting the G7, an anachronistic club in which Canada’s main purpose is to help Washington argue with Germany, France, the United Kingdom and Italy (Japan is the other member).

Let the legacy powers continue to pretend they are running the world without China at the table if they want to. Canada doesn’t need to participate in that charade any longer. We have the future to worry about.

Financial Post

• Email: [email protected] | Twitter: CarmichaelKevin

Copyright Postmedia Network Inc., 2020